Avalon String Quartet: Florence Price and Leo Sowerby: Music for String Quartet

Naxos

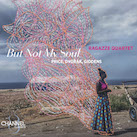

Ragazze Quartet: But Not My Soul: Price, Dvorák, Giddens

Channel Classics

With Avalon String Quartet and Ragazze Quartet including Florence Price's String Quartet No. 2 in A minor (1935) on their respective releases, the urge to assess each in light of the other is well nigh irresistible. Both albums couple Price's work with two others, one by Leo Sowerby plus another by Price in Avalon's case and a Dvorák quartet and Rhiannon Giddens song in Ragazze's. The releases merit hearty recommendations, if for different reasons, and prove to be all the more illuminating when considered side-by-side.

Avalon String Quartet (violinists Blaise Magnière and Marie Wang, violist Anthony Devroye, cellist Cheng-Hou Lee) has been awarded prestigious prizes and issued a number of recordings, one of them Grammy-nominated. But Not My Soul is the ninth album Ragazze Quartet (violinists Rosa Arnold and Jeanita Vriens-Van Tongeren, violist Annemijn Bergkotte, cellist Rebecca Wise) has recorded for Channel Classics, and the group has likewise received acclaim for its performances and collaborations. Both groups, in other words, are well-primed to tackle the set-lists on their respective new releases.

The story of Price's rescue from obscurity is now familiar, and with these albums her ongoing rediscovery continues. Though she wrote almost 400 pieces for orchestra, chamber ensemble, and piano, as well as art songs and arrangements of spirituals, most of the compositions by the Little Rock-born Price were unpublished at the time of her 1953 death. The discovery in 2009 of an abundance of lost pieces was instrumental in seeing her music undergo its current renaissance. The String Quartet No. 2 in A minor presented on these albums was not performed in her lifetime and first published in 2019. Characteristic of her writing, there is European classicism as well as lyrical themes drawn from African American spirituals and folk songs. As one would anticipate, there are commonalities in the two string quartets' handling of Price's four-movement work but differences too, however slight.

After the opening “Moderato” arrests the ear with a chromatic ostinato in the second violin and a less ominous theme in the first, the music swells with a lyrical outpouring before a theme emerges indebted to negro spirituals and then episodes of urgency and yearning. After entering with a ghost-like delicacy, Ragazze's rendering grows ever more luminous and expansive, even at tempestuous moments suggesting kinship with Mahler. While Avalon's delivers the opening ostinato at a slightly faster tempo, the quartet's playing is no less engaging. Theirs is a refined reading that's not without emotional heft, and Avalon's voicing of the folk material is affecting too. One conspicuous difference: Ragazze's is four minutes longer than Avalon's ten-minute version.

“Andante cantabile” is distinguished by a plaintive melody that's presented in a rocking motion, the overall feel gentle, serene, and warm. Both quartets' treatments show sensitivity in dynamics and pacing, though a slower tempo by Ragazze enhances the music's dreaminess. Price's scherzo is set as a juba, a nineteenth-century slave-era dance whose syncopated rhythms are infectious. Avalon and Ragazze enliven the earthy material in equally compelling manner with fiddle-like inflections and bluesy phrasing. “Finale: Allegro” drives the work home with muscular force, rousing dance elements again part of the mix and a calming Andantino surfacing in the middle. While both quartets attack the movement with gusto, Ragazze delivers its rendition with a greater amount of thrust. Comparing these equally credible versions, the impression generally forms that Avalon's is the slightly more refined but also reserved version, Ragazze's a tad more plainspoken and emotionally expressive.

The resilience theme implicitly associated with the Price work extends to the two others on But Not My Soul. The worlds of Price and Antonín Dvorák might seem far apart, but there is, as Ragazze itself argues, kinship between them. It's easily explained: the Czech composer wrote his String Quartet in F Major Op. 96, No. 12—aka the “American”—in the United States, where he'd been invited to research original American music and discovered a treasure trove of material among the black population. Elements thereof materialize in the string quartet and in doing so collapse the temporal and geographical divides between the composers. The concluding piece is At the Purchaser's Option, a Rhiannon Giddens song Jacob Garchik recast for the Kronos Quartet as a string quartet arrangement. She wrote the song after seeing a nineteenth-century advertisement for a young female slave whose nine-month-old baby was also for sale, but “at the purchaser's option” (key lyrics: “You can take my body / You can take my bones / You can take my blood / But not my soul”).

Written about a dozen years after Dvorák's eleventh string quartet, his 1893 “American” enraptures immediately with a singing melody in the opening allegro that establishes an outdoorsy character. The languid passage that follows deepens the idyllic tone before the violist and violinist again pass the opening melody back and forth. While peaceful moments do re-emerge to amplify the romantic tone, the movement largely exudes energetic uplift and hope. The melancholic sorrow of the theme in “Lento” conjures the image of plantation workers singing to ease their burden; animated with joy by comparison are “Molto vivace,” whose fluttering violin figures could pass for birdsong, and robust “Finale—vivace ma non troppo,” which moves at an at times furious clip. Once again, the Ragazze members infuse their playing with dynamism and vibrancy as they bring Dvorák's material to life, and their high-energy execution of the final movement is impressive. At album's end, pizzicato, percussive knocks, and blues-fiddle flourishes make At the Purchaser's Option the memorable set-closer it is. Its tone is not as sombre as one might expect given the story that inspired it, but it's no less engaging for that. At under four minutes, however, the piece is short, which prompts one to wonder whether a more elaborate exploration of the original song wouldn't have been more effective. Being so brief, it seems almost a footnote to the other works.

The two substantial pieces rounding out the Avalon release leave no such impression, however. Leo Sowerby's String Quartet in G minor, H. 226 (1935) isn't the first work by the Michigan-born composer Avalon has performed as two of his string quartets were recorded for Cedille Records in 2021. This one holds the distinction, however, of being the premiere recording of his G minor quartet. As different in musical character as their quartets on this release are, Price and Sowerby were both prominent figures in the Chicago music community in the ‘30s and ‘40s and were apparently aware of and respected each other's work. Like her, his music—more than 500 works in various genres (a cantata brought him the 1946 Pulitzer Prize)—is ripe for rediscovery, and Avalon is doing its part.

Sowerby's quartet doesn't have the immediate appeal of Price's melodically enticing quartet and is also more austere, but it's nevertheless a work of sophistication and quality; it's certainly not lacking for contrast between the four movements either. They're intimated by descriptive titles, the opening “Languidly; darkly – Fast; with dash,” for example, cuing the listener as to what to expect. Consistent with that, it begins broodingly, its eerie aura reminiscent of Bartók, before exposition introduces agitation and urgency and then something akin to lyrical serenity. Contrapuntally rich, the movement makes its way through multiple episodes for nearly fourteen minutes, some foreboding and others introspective. Some moments could even be called Debussy-esque. The “Very fast” scherzo moves with relentless propulsion, though it catches its breath during its slowed middle section before heating up again. “Slowly; rhapsodically” provides five minutes of soothing calm before the multi-faceted closing movement, “(Recitative:) Broadly – (Fugue:) Moderately fast, yet with broad sweep,” arrives.

Ending the album strongly is a second endearing work by Price, Five Folksongs in Counterpoint for String Quartet (1951), which followed her Negro Folksongs in Counterpoint by four years. Familiar melodies bolster the appeal of the 1951 setting, with ones such as “Shortnin' Bread,” “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” and “Oh, My Darling Clementine” instantly recognizable. The spiritual “Calvary” is the seed from which the opening adagio grows, with Price embroidering the melody polyphonically. In “Andantino (Clementine),” the plaintive melody is voiced directly by the violin before being echoed by the other instruments. Whereas the slow central movement exudes a tender melancholy in building itself around the eighteenth-century tune “Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes,” “Allegro (Shortnin' Bread and other folk songs)” lifts the spirits with dance rhythms and an exultant tone. Cello voices the melody first in “Andantino (Swing Low, Sweet Chariot),” after which the tune migrates from one instrument to another, much as it does during the opening movement.

In the final analysis, both albums are worth acquiring, first, for their fine renditions of Price's quartet, and, secondly, in the Ragazze case for coupling it with the Dvorák work and in the Avalon for doing the same with Price's folksongs, though the Giddens and Sowerby pieces also add to the value of the groups' respective releases.April 2024