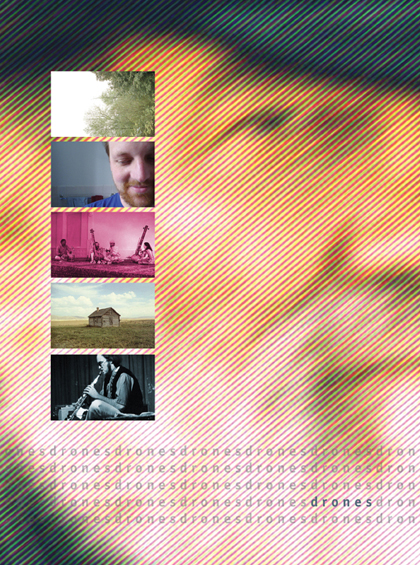

THEATRES OF ETERNAL MUSIC

Say the word drone and, depending on your conversation partner, any number of possible responses might emerge: an entomologist's exegesis on the male honeybee's mating practices, the military expert's account of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, perhaps a musicologist's analysis of the drone-like features of the bagpipe, bluegrass banjo, and didgeridoo. Within electronic music circles, the word might elicit historical anecdotes populated by dramatis personae like La Monte Young and Terry Riley, plus nostalgic recollections colored by strobe-lit chanters and tambura players. Far from being an esoteric phenomenon of the ‘60s, recent works by Greg Davis, Deathprod, Robert Henke, Minit, and Growing suggest that the drone is still very much alive and, if anything, thriving. While there appears to be a resurgence of interest, it's also possible we're merely witnessing new additions to a genre that has never really gone out of fashion.

What constitutes a drone? To begin, sustained intonation that establishes a harmonic center for its accompanying elements; the drone might utilize a single note repeated indefinitely or, at the opposite extreme, all of the scale's notes spread across numerous octaves. Other key aspects include extended duration, modular repetition, and a focus on overtones. Influenced by the music of India, Indonesia, and Africa, the drone form's oft-used alternate tuning (Just Intonation) and vertical concentration challenges the tacit supremacy of a Western tradition that prioritizes horizontal development.

Young and Riley are regularly lumped in with Philip Glass and Steve Reich in discussions of minimalism yet the two pairs embody fundamentally different subsets. According to composer and violinist Tony Conrad, minimal music (of the Young type) involves tonality, repeating modes, and long pieces with middles but no endings or beginnings. Bereft of conventional development, the trance-inducing drone with its extended tones and layered pitches does change but glacially. In lieu of lengthy tones, the early works of Reich and Glass are founded on modal patterns that slowly shift throughout prolonged repetition to a similarly hypnotic effect. One might differentiate, then, between “drone minimalism,” with its tonal emphasis, and “pattern minimalism,” with its rhythmic pulsations. Of course, such theoretical distinctions prove less straightforward in practice. Reich's Four Organs, for example, straddles both drone and pattern variations since its organs repeat the same chord progression for 24 minutes with varying lengths of silence separating the chords. His voice pieces Come Out and It's Gonna Rain serve as better examples given their minimal means, yet here, too, repeating patterns morph into drone-like episodes.

Ambient music and drone genres also overlap, Greg Davis's Somnia drone “Clouds As Edges (version 3 edit)” a case in point. Certainly a piece can satisfy the drone criteria yet be ambient if it also meets Brian Eno's criterion that an ambient work should be “as ignorable as it is interesting” (Music for Airports, 1978). Davis says, “Aside from the more placid, meditative kind of music we often associate with drones, I enjoy that intense style, too, where it's so loud and overwhelming it's completely immersive.” Davis might just as easily be alluding here to the volcanic roar of Young's Theatre of Eternal Music ensemble, Lou Reed's 1975 scabrous feedback fest Metal Machine Music, or the droning riffage of Sunn 0))) and Growing.

Dream Syndicates

Each day, multitudes flock past the unprepossessing entrance to the Dream House, unaware of its musical significance. Located at 275 Church Street in Manhattan's TriBeCa district where La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela moved in 1963, the Dream House functions as an ongoing exhibition and performing space for Young's music and Zazeela's light installations. The loft's white interiors are bathed in Zazeela's colored lights and large speakers emit the ongoing frequencies of Young's drones; sounds resonate more loudly or softly depending on one's position in the room. (Another Dream House was operated from 1979 to 1985 at 6 Harrison Street, a six-story building where Young and Zazeela lived, though they kept the Church Street loft as a legal address.)

No history of drone music is complete without Young, even if voluminous documentation of the artist and his work is available elsewhere. Born in 1935 in a small log cabin in Bern, Idaho to a Mormon family and initially trained on saxophone (he even played with free jazz legend Eric Dolphy), Young discovered Anton Webern, Japanese gagaku, Indonesian gamelan, and Indian classical music upon his 1957 arrival at UCLA. Exposed to the ragas of Ali Akbar Kahn, Young developed a fascination for sustained tones and, with his 1958 landmark composition Trio for Strings (which eschews melody and pulse for static chords and sustained tones), arguably founded minimalism. A 1959 Darmstadt summer course with Karlheinz Stockhausen exposed Young to the radical philosophies of John Cage. (Young's Piano Piece for David Tudor #1, in which the performer offers a bale of hay to his piano to eat and a bucket of water to drink, clearly shows Cage's influence.) Young then moved to New York to study electronic music with Cage and briefly became involved in the Dada-influenced Fluxus movement.

Of course, Young wasn't the first to use the drone—it's fundamental to Indian music—but he can be credited with reviving it within Western classical music. Based entirely on four alternate-tuned pitches, “The Second Dream of the High-Tension Line Stepdown Transformer” from The Four Dreams of China (1962, with a later eight-trumpet version issued on Gramavision in 1991) was his first drone piece in Just Intonation (which substitutes the equal temperament pitches of conventional Western music for tuning that Pythagoras quantified in ancient Greece and is used in many non-Western musics and by composers like Pauline Oliveros and Glenn Branca). With sustained overtones that eventually destabilize the listener's grasp of space and time, its harmonies evoke the electronic hums of hydro wires and power transformers that transfixed Young as a boy.

By 1962, Young was performing with a small ensemble that was eventually christened the Theatre of Eternal Music in 1965; aside from the voices of Young and Zazeela, the group variously included violinist Tony Conrad, violist John Cale, hand drummer Angus MacLise, trumpeter Jon Hassell, violist David Rosenboom, organist-vocalist Terry Riley, and others. Dedicated to realizing Young's The Tortoise, His Dreams and Journeys (an ongoing composition that Young initiated in 1964), the music conflated elements of improvisatory jazz, minimalism, Indian music, and psychedelia into one, with the group's ritualistic (and ferociously loud) bowed-strings-voice improvisations lasting for hours. (Around 1965, Young attached a microphone to his turtle's aquarium motor in order to tune his ensemble to its hum, hence the work's title). Later variations of the Eternal ensemble included the Theatre of Eternal Music Brass Ensemble (led by trumpeter Ben Neill) and The Theatre of Eternal Music String Ensemble (led by cellist Charles Curtis). Young's landmark composition remains The Well-Tuned Piano (the title parodying Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier), a raga-like, multi-tonal (and ongoing) work begun in 1964 and performed in 1981 on a Bösendorfer Imperial grand piano, a performance issued initially on vinyl and then as a five-disc set on Gramavision; that five-hour version is eclipsed by a 1987 performance issued on DVD that better matches the work's six uninterrupted hours (and includes the enhancing spectacle of Zazeela's light sculpture).

Of course, the Theatre of Eternal Music's other members established themselves beyond their association with Young, Terry Riley a case in point. Arguably his most important work, Riley's revolutionary 1964 In C comprises 53 melodic modules that can be repeated as often as desired by an undetermined number of instruments with the piece formally ending once all players reach module 53. In 1997, Conrad issued the four-disc set Early Minimalism: Volume 1, which includes the scorching sustain of 1964's Four Violins plus three 1990's extensions, each album given the name of a month in 1965. (The infamous falling-out between Young and Conrad is well-documented but merits brief mention as it helps clarify why relatively few of the Theatre of Eternal Music's recordings have been issued. Even though many group sessions were recorded, Young has refused to release them despite the protestations of his former colleagues. The discord is rooted in Young's assertion that he is the sole composer of the original performances; the others contend they are co-composers of what were collectively improvised sessions. A recording of the ensemble was issued in 2000, the 31-minute Day of Niagara: Inside the Dream Syndicate, Vol. I and, while the recording's sound quality is abysmal, the document does capture the ensemble's glorious roar and its attempt to “freeze” sound.)

Bridging the Gap

John Cale brought his viola but more importantly Young's concepts to the Velvet Underground before moving on to a storied solo career of great recordings (Fear, Slow Dazzle) and collaborations with Eno (Wrong Way Up) and former VU partner Lou Reed (Songs for Drella). Rather perversely, Reed himself kept the drone flame alive with the 1975 release of Metal Machine Music, two albums of seething noise that outraged his Transformer fans and found them returning to the record stores in droves demanding refunds. (The Loop Orchestra's John Blades says, “I clearly remember it turning up in all the second-hand record shops in Sydney just after it was released” while Greg Davis recalls it playing once in a Chicago bookstore he was working in at the time, much to the bewilderment of the store's customers, one presumes.) The ongoing debate over the work's legitimacy was re-ignited in Berlin, 2002 when the German New Music group zeitkratzer performed the piece live, with Reed joining in on guitar.

Drones awareness spread to prog- and art-rock aficionados with the 1972 release of Tangerine Dream's double-album Zeit (arguably supplanted by 1974's seminal Phaedra) and the 1973 release of No Pussyfooting, comprised of two drones generated by Robert Fripp's guitar and Brian Eno's loops and synths, while krautrock fans discovered Tony Conrad through his Outside the Dream Syndicate collaboration with Faust in 1974 (reissued with a bonus track on Table Of The Elements in 1993). The drones phenomenon held steady throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s due to influential works by the Hafler Trio, :zoviet*france, Nurse With Wound, Phill Niblock, Glenn Branca, Charlemagne Palestine, Earth, Keiji Haino, and others. During the ‘90s, the barren dronescapes of Thomas Köner's gong-generated Nunatak Gongamour and Teimo releases offered a diametric contrast to the comparatively warmer ambient-drone-techno hybrids Zauberberg, Königsforst, and Pop created by Wolfgang Voigt under his Gas guise.

In the early 1980s, Australian radio programmers John Blades and Richard Fielding started experimenting with tape machines by cutting, rearranging, and rejoining pre-recorded tape to generate loops. Developing their ideas further as the Loop Orchestra, the pair made its 1983 debut with four reel-to-reel machines playing slowly evolving constructions. Far from static, the group's loops ebb and flow hypnotically. “I believe our music is only drone-like due to the nature of tape loops,” says Blades. “There is a slow progress and evolution through the duration of a piece, but I prefer the term ambient as this is the effect created by most of our music. After all, the so-called ambient music of Eno (Discreet Music, Music for Airports) is really very dronal.”

In spite of technological advances, the four compositions on 2004's Not Overtly Orchestral were generated using those same reel-to-reel machines. Why do so when newer technologies are available? According to Blades, “We have a great affection for the technology of reel-to-reel machines, a technology which has been largely left behind by the digital age. The machines are beautiful pieces of sculpture; the loops are simple, very organic, and very human. The digital technology is purely a black box and too easy and cold. Also, tape loops and reel-to-reel tape machines are historically significant as the history of electronic music dates back to musique concrete.”

“We're dedicated to creating a body of work that cannot be instantly identified with any past or current movement or style or era,” adds Fielding, “a music that has no patina of contemporariness, no obvious technological or technical development, no mastery of technique, and no mature style.”

Blades says, “We generally try to keep the music as free of associative and identifiable elements as possible. Our first record (released in 1991) included a 20-minute piece called “Suspense” created from tape loops made from suspense and horror movie music from the 1940s to the 1980s (films like Creature From the Black Lagoon); in this case identifiability was part of the intended effect. On the other hand, “Bride” was created using loops from the soundtrack to the 1936 film Bride of Frankenstein; with all the loops layered and the music fragmented, the original score became unrecognizable. It depends on the theme, then, whether loops remain identifiable or not.”

New Practitioners

Asked about current drone artists, Blades says, “At the moment, the most significant artist creating beautiful, intricate layerings of electronic sound is Minit.” The group, formed by Jasmine Guffond and Torben Tilly in 1997, uses sampling, digital processing, and electroacoustic techniques to create meditative soundscapes, four of which are heard to fine effect on the recent Now Right Here. The epic title track is the most impressive, a 20-minute drone whose shimmering tones grow into a dense mass until a bass line appears, anchoring the piece magnificently. While the piece is largely abstract, the timbre and color of its French horns remain readily identifiable. “The use of French horn was instrumental in the process of developing the kind of ecstatic build-up that we wanted,” says Tilly. “Klara Logan played the horn to an already existing bed of sound, and it was her playing that in turn modulated the development of the piece as it leads up to the introduction of the bass line.”

Asked to describe Minit's sound, Tilley says, “When Jasmine and I began the Minit project around 1997, our music was (and to a large extent still is) built almost entirely out of looped samples. Over the last five years, we've attempted to make the loop less obvious, more intricate, and to produce a denser, richer texture, which is perhaps less electronic sounding. The drone works well as a kind of stable firmament under which details can be inscribed and transformations can occur.

“I feel like we are developing our own kind of spectral music, spectral in the sense of paying attention to all the minute details of color and grain within a particular recorded sound. So in a way for us the 'drone' just naturally comes out of this approach, as time and rhythm are sublimated by tone and color.”

Arriving on the heels of Curling Pond Woods' campfire hymns and Beach Boys homages, Davis' Somnia may have caught some listeners by surprise. In fact, the album was created in tandem with his Carpark albums, even if the timing of the releases makes it appear otherwise. (An early version of “Clouds as Edges” was issued as a six-minute single in 2001.) Somnia brings to fruition Davis 's long-standing passion for the genre, an interest that began as early as high school when he discovered Indian classical music, modal jazz, Aphex Twin's ambient works, Reich, and Eno.

Davis bases each Somnia piece on a single instrument yet alters its sound so completely via computer that the result sometimes bears little resemblance to its origins. Speaking between tour stops in Montreal and Boston, he says, “I did constantly ask myself,'‘How far do I take this process?' I was trying to reach the point where the instruments' sound qualities were radically transformed but not beyond the point where you could no longer recognize the original instrument. Its tone color, I believe, is still apparent in the end.” His audacious instrument choices included a bowed psaltery for “Archer” and a toy harmonica for “Diaphanous (edit).”

Describing his production approach to “Archer,” Davis says, “I wanted to create a piece that shimmered with rich overtones, so I sampled myself playing every diatonic note on the bowed psaltery, and then used a Max/MSP patch to generate a drone, which I then processed towards its final form.” Even more arresting are the whistles and moans of “Mirages (version 2)” that were generated from a Schaaf punch-card music box (which generates sounds when holes are punched out of staffs displayed on cardboard strips and then fed into the music box). “Using music box samples, I wanted to transform the stereotypical associations we have with music boxes,” he says, “and using spectral graphical processing and resynthesis techniques, ended up creating a haunted quality.”

Somnia not only includes long tracks like the 22-minute “Campestral (version 2)” but also short pieces like the 4-minute “Furnace.” “I struggled a lot with song duration and album length,” Davis admits. “‘Campestral' had a long melody to begin with, and with time-stretching, transposing, and layering, it ended up being a naturally longer piece. At the same time, I liked the idea of incorporating shorter pieces to show that an immersive and effective drone can still be created in four minutes.” His interest in the project extends to the stage as well. “Each night I've been creating a new piece using real-time processing on one of the instruments I've brought on tour (bells, glockenspiel, harmonica, melodica, stylophone, Egyptian double reed flute, gongs, farfisa, autoharp, guitar, et cetera),” he says. “Sometimes I'll also incorporate field recordings and improvisations into the live tapestry.”

Robert Henke (a.k.a. Monolake) shares Davis ' enthusiasm for bringing drone material to the stage, although for him the ideal scenario for presenting Signal to Noise would be a multi-channel setup with the audience completely surrounded by sound. Even though the drone is most powerfully experienced live (as its duration isn't determined by album running time), the two slowly mutating works on Signal to Noise are definitely immersive. For the album's 32-minute title piece, Henke used a Yamaha SY77 to generate timbres he then filtered, pitch-shifted, and processed to create drifting, wave-like clusters, while static bursts and rumbles on the more programmatic “Studies for Thunder” were sculpted to mimic thunderstorms. Henke's interest in drones stems from a fascination with gradually evolving structures, even if their forms are different: “For me, a pulsating, repetitive club track, the music of Steve Reich, a Thomas Köner soundscape, or distant urban traffic noises are all equal sources of inspiration and delight.”

While Davis 's Arbor and Curling Pond Woods are on Carpark, Chicago-based kranky seems the more fitting home for Somnia given the label's roster of drone-related artists like Stars of the Lid, Charalambides, and Growing. By the title alone, Growing's most recent album, The Soul of the Rainbow and the Harmony of Light, begs associations with Young and the psychedelicized ‘60s period, even if the title derives from an 1893 essay by Bainbridge Bishop on his 1877 color organ invention (a device capable of playing sound and corresponding light together or separately). While group members Kevin Doria (bass and guitar) and Joe Denardo (guitar) embrace the drone's primal power (the roar of “Anaheim II,” for example), their seething shards of guitar and waves of delay are loud but not dissonant or cacophonous; their “ambient doom” sound is rapturous, elemental in force and ethereal in effect. The album opens with “Onement,” an 18-minute epic of shuddering guitars, harmonium-like drones, and cymbal noise that eventually engulfs all other sounds. The harmonium sound reappears in the more incantatory “Epochal Reminiscence,” where crystalline tones appear alongside gargantuan guitar slabs.

The group's interest in drones is evident on its 2003 debut The Sky's Run Into The Sea but that interest emerged long before. As a developing bass player, Doria gravitated towards artists like Sonic Youth, Earth, Glenn Branca, Young, Riley, and Pandit Pran Nath; likewise, Denardo was captivated by Earth's 1993 Earth 2 special low frequency version (Sub Pop) and he's “still wearing out the grooves on (Terry Riley's organ improvisation) Persian Surgery Dervishes.” In addition, he says, “It's always wonderful to see Sunn 0))) play, to feel its awesome power.” When asked about memorable drone-related experiences, Denardo cites a visit to the Dream House, and in doing so echoes Davis, who visited there with Keith Fullerton Whitman and David Grubbs.

An Eternal Voice

The sum total of artists working in drone-related genres is immense, as evidenced by an inquiry into the practitioners' favorites. In addition to Minit, Blades cites Brendan Walls and Scott Horscroft; Fielding's eclectic list includes Birchville Cat Motel, the Dead C, the Master Musicians of Joujouka, Harvest Music of Chad, Tuvan throat singing, Inuit women, and Sufi music. Tilley says, “I'm very interested in what Radian is doing, because the group is merging the sonic and spectral with the rhythmic and melodic.” Greg Davis cites the impact of Alvin Lucier's Music on a Long Thin Wire and The Tamburas of Pandit Pran Nath and mentions Rafael Toral, Fennesz, Hazard, Keith Fullerton Whitman, Growing, and more in a long list of favored contemporary drone artists.

Given the fervent level of artistic enthusiasm for the genre, one wonders if there has been a surge of recent interest. Davis contends that there have always been practitioners even though current technologies allow drone music to be more easily produced, a sentiment shared by Henke and Denardo. “There have always been practitioners but, even more than the media deciding what to cover, I think the ‘listening public' is paying attention,” says Denardo. “In certain parts of the country, people consistently come to our shows, and Earth and Branca have never stopped doing this type of music.” Henke similarly notes the media's intermediary role as a factor: “If you are a music journalist and on your table are ten Eurotrance CDs and one drone record, which one will you remember?”

“The resurgence of interest in drones goes hand-in-hand with a resurgence of interest in minimalism,” says Blades. “In recent years, there has been an increase in total listening, and drone listening requires total immersion in the sound environment. I also believe that, with the global atmosphere of violence and terrorism, meditative and total listening experiences are more highly regarded.” Blades cites artists like :zoviet*france, Hafler Trio, Nurse With Wound, Bernhard Gunter, Oren Ambarchi, and Phill Niblock as carrying on the drone tradition.

Why does the drone have such enduring appeal? “Its music and sound environment is very minimal and pure, devoid of fashions or trends like glitch,” says Blades. Another factor is its vast spectrum of stylistic possibilities, that it can simultaneously accommodate the unearthly, funereal epics of Deathprod's Morals and Dogma and the stately beauty of Jóhann Jóhannsson's Virðulegu forsetar. Maybe its longevity is rooted in something more primal: Denardo says that the most inescapable drones (and those which keep us from any true silence) are the low pulses of our circulatory systems and the high hums of our nervous systems. Or perhaps, as Davis says, it's because “the drone is the eternal voice of the universe.”

Further Reading :

Four Musical Minimalists by Keith Potter (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Minimalists by K. Robert Schwartz (Phaidon, 1996).

“Dream Encounters: La Monte Young meets Mark Webber,” The Wire, December 1998, issue 178.

“Early Minimalism,” The Wire, April 2001, issue 206.

“Inside The Dream Syndicate,” The Wire, April 2001, issue 206.

Web info:

Greg Davis

Growing

Robert Henke

Loop Orchestra

Minit

Just Intonation/Kyle Gann

La Monte Young/MELA (Music Eternal Light Art) Foundation

Further Listening:

Greg Davis: Somnia (kranky)

Growing: The Soul of the Rainbow and the Harmony of Light (kranky)

Robert Henke: Signal to Noise (Imbalance)

The Loop Orchestra: Not Overtly Orchestral (Quecksilber)

Minit: Now Right Here (Staubgold)

John Cale: Day of Niagara: Inside The Dream Syndicate, Vol. I (Table of the Elements)

John Cale: Dream Interpretation: Inside The Dream Syndicate, Vol. II (Table of the Elements)

John Cale: Stainless Gamelan: Inside The Dream Syndicate, Vol. III (Table of the Elements)

John Cale: Sun Blindness Music (Table of the Elements)

Tony Conrad: Early Minimalism, Vol. 1 (Table of the Elements)

Tony Conrad (with Faust): Outside The Dream Syndicate: 30th Anniversary Ed. (Table of the Elements)

Terry Riley: In C (Sony)

Terry Riley: In C: 25 th Anniversary Concert (New Albion)

Terry Riley: Persian Surgery Dervishes (NewTone)

La Monte Young: The Melodic Version of The Second Dream of The High-Tension Line Stepdown Transformer from The Four Dreams of China (Gramavision)

La Monte Young: The Tamburas of Pandit Pran Nath (Just Dreams)

La Monte Young: Theatre Of Eternal Music (Shandar)

La Monte Young: The Well-Tuned Piano (Gramavision)

Related Listening:

The sheer number of drones-related recordings verges on astronomical but a representative list might include:

Glenn Branca: Symphony No. 5 (Altavistic)

Charalambides: Joy Shapes (kranky)

Rhys Chatham: An Angel Moves Too Fast to See,

Selected Works: 1971-1989 (Table of the Elements)

Deathprod: Morals and Dogma (Rune Grammofon)

Stuart Dempster: Underground Overlays from the Cistern Chapel (New Albion )

John Duncan: Phantom Broadcast (Allquestions)

Earth: Earth 2 special low frequency version (Sub Pop)

Faust: Ravvivando (Klangbad)

Fripp and Eno: No Pussyfooting (Eeg)

Fushitsusha: The Wisdom Prepared (Tokuma)

Gas: Zauberberg (Mille Plateaux)

Philip Glass: Music in Twelve Parts (Nonesuch)

Keiji Haino: So, Black Is Myself (Alien8)

Harmony Rockets: Paralyzed Mind of the Archangel Void (Big Cat)

Ryoji Ikeda: Matrix (Touch)

Jóhann Jóhannsson: Virðulegu forsetar (Touch)

Thomas Köner: Nunatak Gongamour (Barooni)

Alan Lamb: Primal Image (Dorobo)

Jean-François Laporte: Mantra (Metamkine)

Alvin Lucier: Music On A Long Thin Wire (Lovely Music)

Roy Montgomery: Scenes From The South Island (Drunken Fish)

Phill Niblock: Young Person's Guide to Phill Niblock (Blast First)

Nurse With Wound: Soliloquy For Lilith (Idle Hole)

Pauline Oliveros: Deep Listening (New Albion)

Jim O'Rourke: Happy Days (Revenant)

Paul Panhuysen: Partitas For Long Strings (XI Records)

Charlemagne Palestine: Schlingen-Blangen (New World)

Pelt: Empty Bell Ringing in the Sky (Vhf)

Folke Rabe: What?? (Dexter's Cigar)

Steve Reich: Early Works (Nonesuch, includes Come Out and It's Gonna Rain )

Steve Reich: Four Organs/Phase Patterns (NewTone)

Janek Schaefer: Above Buildings (Fat Cat)

Stars of the Lid: The Tired Sounds of (kranky)

Sunn 0))): Flight Of The Behemoth (Southern Lord)

Sunroof!: Bliss (Vhf)

Tangerine Dream: Zeit (Sanctuary/Castle)

Rafael Toral: Violence of Discovery and Calm of Acceptance (Touch)

David Tudor: Rain Forest (Mode Records)

Vibracathedral Orchestra: Dabbling With Gravity & Who You Are (Vhf)

Windy & Carl: Consciousness (kranky)

Richard Youngs: Advent (Jagjaguwar)

:zoviet* france: The Decriminalisation Of Country Music (Tramway)

February 2005

![]()