LIVE PERFORMANCE IN THE AGE OF SUPER COMPUTING (PART 1)

by Robert Henke

(Henke photos: Miguel Legault)

Certainly within the electronic music community, Robert Henke needs no introduction. Not only has he contributed profoundly to the genre's evolution with Monolake releases like Hong Kong, Interstate, Cinemascope, Momentum, and others, his recent Layering Buddha (issued under his own name) received an Honourable Mention at the prestigious Prix Ars Electronica competition in the Digital Musics category. Equally importantly, Henke has dramatically advanced the music's development with his globally-renowned Ableton Live software. A veteran performer, Henke recently composed an article about the experience of playing live using digital technologies which he published at his Monolake site, and we are delighted to now feature it at textura too. What follows is the article's first part; the second will appear at the Monolake site and at textura in the near future.

Introduction

Lots of things have been written and said about live electronics, especially since so many of us are occupying the stages of clubs and festivals with our laptops. As a description for this kind of concert, the term laptop performance was invented, probably by journalists who were desperate to find a catchy icon for what they saw and could not categorize. I do not like that term so much; to me, the laptop is just another musical tool and the only reason why I am using it on stage is the simple fact that it is a portable supercomputer, capable of replacing huge racks of hardware.

Moog Synthesizer

The laptop itself does not contribute anything on its own; we do not write a Symphony for Dell, perform a Suite for Six Vaios or Two Crashes for Power PC, unless we want to be very ironic. What makes it an instrument is the software running on it, and this is where things start to get complicated. The audience looks at a laptop while listening to music, but what exactly creates the music and how the performer interacts with this tool is completely non-transparent. The laptop is not the instrument; the instrument is invisible. And to obscure things even more, we have to realize that most of the time there is not one single instrument and it is not ‘played' by the performer. What really happens and what remains completely undecodable for the audience is more described as a huge number of instruments played by an invisible band sitting inside the laptop. The only visible part is the performer conducting the work in a way that looks extremely boring in comparison to the amount of physical work carried out by the guy forcing a full-blown orchestra of stubborn professional musicians through a symphony. The minimum difference between pianissimo and a wall of noise? One pixel, 0.03mm.

Contributing to the miracle called laptop live act is the fact that the audience would not even derive much useful information from the knowledge of what software is running on that computer, since in most cases the software used for performing is not the same as the one used for creating the music. Even if it is, the process of performing is quite different from the process of composing. If we want to get a clue as to what goes on when someone plays a laptop on stage, we need to dive deeper here, deeper into technology and into the history of electronic music. By doing so, we might get a more precise idea of it all.

Chapter I: The Invisible Instrument

Every time someone asks me what I do for a living and I answer that I make music, the inevitable follow-up question is about what instrument I play. I always get red and mumble “computer,” anticipating spending the next half hour with explanations. (Due to my occupation with Ableton, I nowadays can say that I am a software guy, and there are usually no further questions.)

How do you play a computer? Rhythmically banging on the LCD screen? With a bow? With a hammer? (Sometimes!) The strange look one gets when admitting to playing a computer indicates that this instrument does not fit into the known world of instruments so much.

Why is this?

A classical non-electronic musical instrument relies on a constant user-interaction in order to produce a sound. The instrument has specific physical properties, defining its sound and the way it wants to be played. The music is a result of the properties of the instrument and the skills of the player. Listeners have a sense of what goes on, even if they do not play any instruments themselves. It is obvious that a very small instrument sounds different from a very big one, that an orchestra sounds most massive and complex if everyone involved moves a lot, and that hitting a surface with another surface creates some sort of percussive effect, depending on the nature of the material. A whole world of silent movie jokes is based around this universal experience and knowledge. If hitting a head with a pan produces a ‘boioiooioioioioioggggg,' the comical element is the mismatch between expectation and result. Now, explain to someone why pressing a space bar on a computer sounds like Bruce Springsteen one time and, the next time you try, it makes no sound at all. With ‘real' instruments, it is also obvious that precision, speed, volume, dynamics, richness, and variation in sound are the result of hard work, and that becoming a master demands training, education, and talent. Without the player doing something, there is nothing but silence.

There are exceptions to this rule, and it is no surprise that these instruments have some similarity to electronic instruments. Consider for example a church organ, which allows the performer to put some weight on the keys, and enjoy the resulting cluster of sound without further action, or the mechanical music toys capable of playing back compositions represented as an arrangement of spikes on a rotating metal cylinder. The church organ already is a remarkable step away from the intuitively understandable instrument. The organ player is sitting somewhere, and the sound comes from pipes mounted somewhere else. Replace the mechanical air stops by electromagnetic valves, and, at some point, the player by a roll of paper with punched holes, and the music can be performed with more precision than any human player could achieve.

Player Piano, 1920

The image above shows an Ampico-Player Piano from Marshall & Wendell made in the 1920s. It was used by composer Conlon Nancarrow to realize compositions unplayable by humans. The invention of electricity made much more complex ‘self-playing' instruments possible and, due to further technological progress in electronics and computer science, those machines became small enough to be affordable and sonically rich enough to make them interesting for composers. Nowadays, two main types of electronic instruments exist: those which are made for classical instrumentalists, mostly equipped with a mechanical keyboard, and those for the composer, allowing for recording, editing, and manipulating music. And all kinds in between.

If you replace a musician by a sound-generating device directly controlled by a score, you get rid of the unpredictable behaviour of the human being and you gain more precise control over the result. A great range of historical computer music and certainly a huge portion of the current electronic (dance) music has been realized without the involvement of a musician playing any instrument in real time. Instead, the composer acts as a controller, a conductor, and a system operator, defining which element needs to be placed where on a time-line. This process is of an entirely different nature from actually performing music, since it is a non-real time process, and is therefore much closer to architecture, painting, sculpting, or engineering.

Roland TR-808

During the creation of electronic music, this non-real time process allows for an almost infinite degree of complexity and detail, since each part of the composition can be modified again and again. New technologies make this possible to a previously unthinkable extent. We now live in a world of musical undo and versioning. A computer is the perfect tool for these kinds of operations, capable of storing numerous versions of the same work, and also allowing for extreme precision in detail. The general workflow is much more efficient than the complex classical studio setup, with a giant mixing desk, and lots of hardware units and physical instruments, even with ten assistants running around all of the time. The result of working for several weeks with music software might be a piece of audio which is the equivalent of two hundred musicians, five huge racks of different effects units, and massive layering of instruments—very impressive, indeed. So, now go, put this on stage...

Chapter II: The Tape Concerts

At the very beginning of computer music, the only way to perform a concert was to play back a tape. The so-called tape concert was born, and the audience had a hard time accepting the fact that a concert meant someone pressing a play button at the beginning and a stop button at the end. Ironically, half a century later, this is what all of us have experienced numerous times when someone performs with a laptop. Trying to re-create a complex electronic composition live on stage from scratch is a quite absurd and, most of the time, simply impossible task.

Ampex Tape Recorder

The bottleneck is not that today's computers cannot produce all those layers of sound in real time, but that one single performer is not able to control that process in a meaningful and expressive way. Even if someone owned all of the instruments of an orchestra and even if that person is capable of playing them all, it is obviously impossible for this person to perform a symphony alone.

The computer musicians of the mid-20th century had no alternative: the tape concert was the only way to present their work, since all computer-generated music was realized in a non-real time process; the creation of the sound took much longer for the computer to calculate than the duration of the sound itself—a situation which, for the design or modification of more complex sounds, was quite normal until a decade ago. This explains why the whole topic of live performance with nothing but a laptop is so new. Even back in the 1930s, there were already real time electronic instruments such as the Theremin or Oskar Sala's Mixtur Trautonium. Built for a single player and by nature in expresssion and approach similar to acoustic instruments, their complexity nevertheless was limited and they were never meant to replace a full orchestra with one machine. For our purpose of finding ways out of the laptop performance dilemma, the tape concert situation is of much more interest since it is closer to what we do with our laptops today.

Leon Theremin

Even while these concerts were referred to as tape concerts, there was the notion of the speaker as the instrument. The speakers were what the audience could see, and then there was the operator with his mixing desk and the tape machine. The speakers were located on stage, replacing the musicians, while the operator was sitting in the middle of the audience or at the back of the room but not on stage. Visually, it was clear that he was not the musician but the operator. There was a very practical reason for this. Similar to the role of the conductor, the operator was the person controlling the sound of the performance, and this could only be done by a placement close enough to the audience. This became even more important once composers started to use multiple speakers.

Multiple speaker tape concerts soon became situations with room for expression by the operator. A whole performance school is based around the concept of the distribution and spatialization of stereo recordings to multiple, often different sounding speakers, placed all around the listener. The operator, similar to a good DJ, transports the composition from the media to the room by manipulating it. The DJ mixes sources together to stereo, and the master of ceremony of a tape concert distributes a stereo signal to multiple speakers dynamically to achieve the most impact. This can be a quite amazing experience, but it certainly needs the operator to be in the eye of the storm, right at the center of the audience.

Francois Bayle performing with the Acousmonium, a multi-speaker arrangement he invented in 1974

The DJ concept has a connection to the tape operator concept: both take whole recorded pieces and re-contextualize them, one by diffusion in space, and the other by combining music with other music. No one in the audience listening to a choir on a record assumes that, at the moment she experiences that choir, some very tiny little singers are having a good time inside a black disk of vinyl. We all know what goes on and we judge the DJ by other criteria than the intonation of the micro-choir inside the record. A good DJ set offers all we normally expect from a good performance. We can understand the process, we can judge the skills, and we can correlate the musical output to input from the DJ; we have learned to judge the instrument ‘turntable and mixer.' The same is true for the distribution of pre-recorded music to multiple speakers. There is a chance we understand the concept and this helps to evaluate the quality of the performance more independently from the quality of the piece performed.

Also a classic tape concert typically is annotated with some kind of oral introduction or written statement, helping the audience to gain more insight into the creation of the presented work. I find this kind of concert situation quite interesting and I think it still could serve as a model for today's presentation of various kinds of electronic music. However, while in the academic music world tape concerts are well accepted and understood, there seems to be a need for electronic music outside that academic context to be ‘performed live' and ‘on stage,' regardless of whether this is really possible or not. The poor producer, forced by record labels and his own ego, or driven by the simple fact that he has to pay his rent, has to perform music on stage which does not initially work as performance, and which has never been ‘performed' or ‘played' during the creation at all.

When listening to one of those more or less pre-recorded live sets playing back from a laptop, we have almost no idea of how to evaluate the actual performance, and we might want to compare a completely improvised set (which is indeed also possible now with a laptop if you accept reduced complexity of interaction) with a completely pre-recorded set. We have no sense for the kind of work carried out on stage. What we see is that glowing apple in the darkness and a person doing something we cannot figure out even if we are very familiar with the available tools. This scenario is not only unsatisfying for the audience but also for the performing composer. The audience cannot really judge the quality of the performance, only the quality of the underyling musical or visual work, but it might be fooled by a pretentious performer, might compare a complete improvised performance, full of potential failure, with a presentation of a pre-composed and perfectly well-balanced work, without being able to distinguish the two. Also, the performer himself might want to be more flexible, might want to interact more, or at least might feel a bit stupid alone with his laptop on a fifteen-meter long, five-meter deep stage with the audience staring at him, expecting the great show which he will not deliver.

The classical tape concert, is an option which works well for scenarios where pre-recorded pieces are presented, and this is made clear to the audience and where there is room for the operator in the center or at least close to the audience and in front of the speakers. For those reasons, it does not really work in a normal dance club context, or as a substitute for a typical rock'n'roll style ‘live' concert. If the tape concert is not an option, the key questions are: how can I really perform and interact on stage and, how can I make the audience aware of what goes on without having them read a long statement or start the concert with a ten-minute introduction?

Chapter III: The Golden Age Of Hardware

Historically, academic computer music is closely connected to research in instrument and interface design. And the typical concert audience appreciates or at least accepts experimental setups of all kinds, even if the result might be not 100% satisfying. I remember a concert years ago in a church during a computer music conference. In front of us on tables was a battery of Silicon Graphics computer workstations, and racks full of electronics of unknown origin.

Data Glove

The estimated value of all that equipment surely exceeded the value of the church building itself by far. Lights were turned off, the spotlight came on, five performers took their seats behind the screens, and the audience waited in silent expectation while the performers prepared for things to come. There then came the sound of concentrated hacking on computer keyboards, occasional clicks of a mouse, and then finally one of the guys raised his left hand, armed with a new interface device called a data glove. As a result of a sudden dramatic gesture with his hand, with maybe a one second delay, some loud and piercing sound emerged from the speakers, a long digital version of a meowing cat or something like it, unfortunately not embedded in mild clouds of reverb. The performers continued to stare at their screens, with occasional mouse and keyboard actions, while the one with the glove made more and more dramatic gestures, all leading to various cat sounds like moouuiiiiiooooooooouuuussssss, each time involving this one second between the movement of the tactile device and the output of the sound.

miiiioooouuuuuuuuuuiiiiiooooooooooooooooo................iuiuiuuiuiuiuiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii.......... Most of the audience seemed not to find this particularly strange or funny but I had a hard time not laughing out loud. And I was not even stoned. Data gloves did not make their way into the mainstream music scene, but obviously a performer doing something dramatic on stage which leads to a comprehensible musical result had potential.

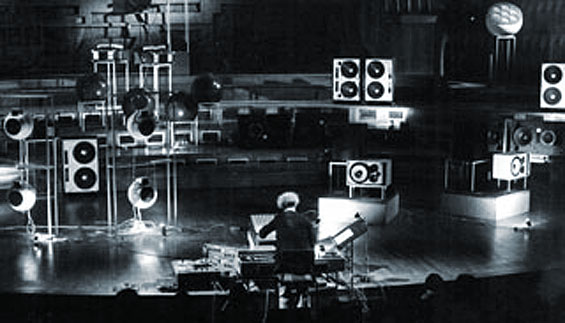

While the creation of academic computer music was, from the very beginning, more of a non-real time process than an actual performance, the late sixties saw the development of the first commercial synthesizers, equipped with a piano keyboard, and ready to be played by musicians rather than operated by engineers. Suddenly, electronic sound became accessible to real musicians; this led not only to impressive stacks of Moog, Oberheim, Yamaha, and Roland keyboards on stage but also to a public awareness and notification of electronically-created sounds. The peak of this development was the stage shows of electronic post-rock bands like Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk in the late seventies and early eighties.

What the audience saw was a bunch of people hidden behind impressive amounts of technology, blinking lights, large mixing consoles, and shimmering green computer terminals ... a showcase of the future on stage. It was impossible to understand how all these previously unheard-of new sounds emerged from the machines, but due to the simple fact that there were masses of them and total recall was not possible, the stage became a place where a lot of action was needed throughout the course of the performance. Cables had to be connected and disconnected from modular synthesizers, faders had to be moved, large floppy disks were carefully inserted into equipment most people had never even seen before, and more complex musical lines still had to be played by hand. It was a happening, an event, remarkable and full of technological magic; the concert was a unique chance to experience the live creation of electronic music. And it was live. What was set up on stage was nothing less than a complete electronic studio, operated by a handful of experts in real time. Great theatre, great pathos, and sometimes even great musical results.

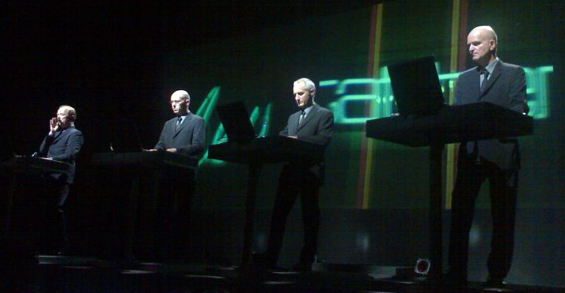

Kraftwerk (2005)

The giant keyboard stacks and effects racks not only looked good on stage, they were the same kinds of instruments as the ones used in the studio during the creation of the recordings preceding the live concerts. Putting them on stage was the most straightforward and clear way to perform electronic music and, since they were so incredibly expensive, the costs of transport and maintenance did not matter so much. If you could afford these tools you probably sold enough albums to pay for transportation and to attract enough people for a stage show. The classical rock scenario, music for the masses. This is the past, the golden age of electronic super groups and the times of super-expensive hardware. Starting from the late 1980s, inexpensive computer technology changed things dramatically. Creating electronic music became affordable for a broader range of people with the advent of home computer-based MIDI sequencing. This not only had an influence on the process of creation but also on performance.

Chapter IV: Fame and Miniaturisation

If the creation of electronic music is possible in a bedroom, it is also possible to put the content of this bedroom (minus the bed) on stage. Or right from the trunk of a car down to a dance floor or temporal concert space established in the basement of an abandoned warehouse, without a stage, right in front of the audience, preferably close to the bar. The revolutionary counterpoint to the giant stage shows of the previous decade was the low-profile, non-stage appearance of the techno producer in the early nineties. The equipment became smaller and the distance between performer and audience became smaller too. I remember nights in Berlin clubs at this time, where I spent my time watching guys operating a Roland TR-808 drum computer or muting patterns on a mixer or in their sequencers on their Atari computers. The music was rough, and its structure was simple enough to be decodable as the direct result of actions taken by the performers. Flashing lights on mixer, all fingers on mutes, eye contact with the partner, and here comes the break! Ecstatic moments, created using inexpensive and simple-to-operate equipment, right in amongst the audience. Obscure enough to be fascinating, but at the same time an open book to read for those interested, and in every case very direct and, yes, live!!

It's the tragic effect of history that these moments come to an end, driven by the same forces enabling them in the first place. Computers became cheaper and more powerful, and more and more complex functions could be carried out hidden in a small box.

This development changed electronic live performance in significant ways. The more operations that a computer in the bedroom studio was able to carry out, the more complex the musical output could be, and the less possible it was to re-create the results live. A straight techno piece made with a Roland TR-808 and some effects and synth washes can be performed as an endlessly varying track for hours. A mid-‘90s drum'n'bass track, with all its time stretches, sampling tricks and carefully-engineered and well-composed breaks is much harder to produce live, and marks pretty much the end of real live performance in most cases. To reproduce such a complex work, one needs a lot of players, unless most parts are pre-recorded. As a result, most live performances became more tape concert-like again, with whole pieces played back triggered by one mouse click and the performer watching the computer doing the work.

This would all be fine, if performance conditions reflected this, but obviously it does not happen in most cases. Instead, we experience performers who are more or less pretending to do something essential or carrying out little manipulations of mostly predefined music. The performer becomes the slave of the machine, disconnected from his/her own work as well as from the audience, which has to do with the second big motor of change: fame. Fame puts the performer on stage, away from the audience. Miniaturisation puts the orchestra inside the laptop. Fame plus miniaturisation works very effectively as a performance killer.

When I started playing electronic music for audiences it was always in a very non-commercial situation, and I enjoyed this a lot. People came because of the music and not because there was a big name on a poster. Being close to the listeners enhanced the feeling of being part of a common idea.

Robert Henke, MUTEK 2007

That intimacy provided a highly communicative situation, where interaction with the audience was possible, if not desired. But once you reach a certain level of fame, it does not work anymore; the electronic artist, now internationally known after all the years in a musical underground, performs on stage and not next to the bar on a small table. The audience wants to be overwhelmed, they want to experience the idol, not the guy next door. The audience expects from a concert the same full-on listening experience as from records. And this is impossible to deliver in real time. But the star has not so much of a choice. He or she plays back more or less pre-recorded music. From a laptop. Far away from the audience. Elevated. Lonely.

Instead of letting the audience experience the great world of creating electronic music live, and instead of being capable of interacting spontaneously, the artist watches the music passing beneath the time line, and tries to make the best out of it by applying effects.

This situation not only leads the audience to conclude the person on stage might be checking e-mail or flight times, but it is also extremely unsatisfying for the performer. Performing electronic music on a stage without acoustic feedback from the room, completely relying on some monitors, is quite a challenge and most of the time far from fun for the artist. The sound would be so much better if we on stage could hear what the audience hears. The most horrible situation you can find yourself in is the classic rock setup. Two towers of giant speakers, bad floor monitors, and a lonely performer behind a table, obscured by smoke, hiding behind the laptop. Usually, no sound guy in the audience who has any real idea of what you're going to do or how you want it to sound, and no band colleagues who could provide some means of social interaction; instead, there is just you and your laptop. The best recipe to survive this is to play very loud, with very low complexity and hope for an audience in a chemically-enhanced mode.

Unfortunately, most typical concert situations outside the academic computer music community do not support the idea of playing right in the middle of the audience. In a club, it is often impossible since there is the dance floor and you do not want to be right in there with a laptop on a small table at four in the morning, and even if you do find a situation appropriate for a centered performance, maybe at a festival, after successfully arguing with a sound technician for several hours you might be confronted with the dynamics of the expectations of fans: They want you elevated, they want you on stage, they want to look up to you, they want the show they are used to, and no ‘weird experimental setup.'

There is an interesting difference between the computer music presenter and a live act. While the centered tape operator has perfect conditions for creating the best possible sound, for presenting a finished work in the most brilliant way (which might occasionally even include virtuoso mixing desk science rather than static adjustment to match room acoustics), the live act has to fight with situations which are far from perfect and at the same time is expected to be more lively. Given these conditions, it is no wonder that generally rough and direct live sets are more enjoyable, while the attempt to reproduce complex studio works on a stage seem more likely to fail.

A rough-sounding performance simply seems to match so much more the visual information we get when watching a guy behind a laptop. Even if we have no clue about his/her work, there is a vague idea of how much complexity a single person can handle. The more the actions result in an effect like a screaming lead guitar, the more we feel that it is live. If we experience more detail and perfection, we most likely will suspect we are listening to pre-prepared music. And most of the time we are right with this assumption.

We could come to the conclusion that only simple, rough, and direct performances are real performances; we could forget about complexity and detail and, next time we are invited to perform, we could grab a drum computer, a cheap keyboard, a microphone, and make sure we are really drunk. It might actually work very well. But what is to be done, if this it is not what we want musically?

This article first appeared at Robert Henke's Monolake site. Many thanks to Robert for generously granting permission for the article to be published at textura.

September 2007![]()