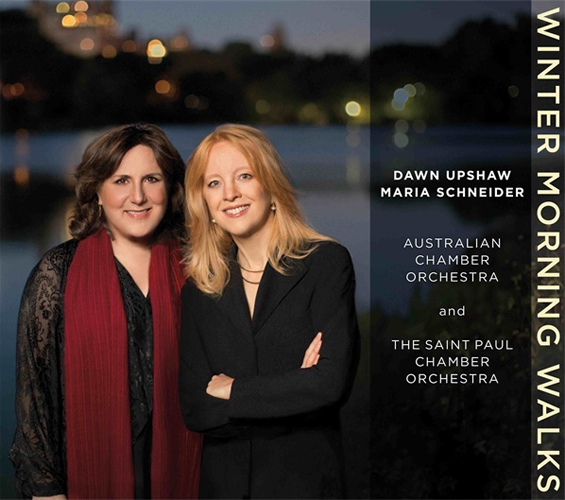

photo: Jimmy and Dena Katz

TEN QUESTIONS WITH MARIA SCHNEIDER

Born in Minnesota in 1960, composer-arranger-conductor Maria Schneider has enjoyed a remarkable and illustrious career. After earning her Masters of Music from the Eastman School of Music in 1985, she worked as Gil Evans' musical assistant for three years and studied with Bob Brookmeyer for five before establishing the seventeen-member Maria Schneider Jazz Orchestra in 1993 and carrying on the Ellingtonian tradition of composing pieces with specific soloists in mind. Critics have described her orchestral-jazz music as “evocative, majestic, magical, heart-stoppingly gorgeous, and beyond categorization.”

Though she's issued a modest seven albums since the release of Evanescence in 1994, each of those albums is distinguished by the immense effort and care that went into its creation. Her efforts have been rewarded with multiple awards, among them Grammy Awards for “Best Large Jazz Ensemble Album” in 2004 for Concert in the Garden and “Best Instrumental Composition” in 2007 for “Cerulean Skies” from Sky Blue; Schneider also was honoured as “Best Jazz Composer” and “Best Arranger” in DownBeat's Annual Critics' Poll in 2010, 2011, and 2012. Honoured with three 2014 Grammy awards (“Best Contemporary Classical Composition,” “Best Classical Vocal Solo,” and “Best Engineered Album, Classical”), her most recent recording, Winter Morning Walks (reviewed here) presents a bold new direction for Schneider: its two orchestral works are vocal-based settings whose texts are drawn from the writings of Pulitzer Prize winner Ted Kooser and Brazilian poet Carlos Drummond de Adrade and sung by esteemed soprano Dawn Upshaw—a sumptuous album that's amply deserving of the praise it's received since its 2013 release. In a recent interview with textura, Schneider spoke about the album in detail, her associations with Evans and Brookmeyer, and the challenges facing a composer in the internet age. It is an honour to feature an artist of Schneider's calibre in textura's pages, and we sincerely thank her for taking the time to speak with us.

1. Long ago you studied composition with Bob Brookmeyer and were even a musical assistant to Gil Evans for three years. Is their influence still present in your music today (and in what way specifically), even though it's been decades since you had those particular associations with them.

One could aspire for a lifetime to the greatness of these men. Bob's incredible skill at development is absolutely astounding and unparalleled—the way he could take a simple idea and morph it into so many different things, but making everything all flow so naturally and feel united. It's all so ingeniously constructed, yet it never feels forced. He did that in his improvisation and he did that in his composition. With Gil, his sense of ‘line' is, in my opinion, also unparalleled. Every single member of an orchestra playing his music always has a beautiful melodic contour, even the tuba. Gil wrote music full of tremendous detail that yet never feels cluttered. It's detailed, yet direct and simple somehow without being simplistic. I love those aspects of each of these men, and surely those things influence me on a continual basis, even if I would never claim to even come close to doing in these respects to doing what these men did.

2. In the liner notes to Winter Morning Walks, you state, “In setting poems to music, the poems themselves speak the rhythm, etch the melodic contour, and emotionally elicit the harmony.” Did you find that having the poems as a starting point made the composing process easier, as opposed to started out with a blank canvas in front of you, or were there times when you found yourself longing to be free of the delimiting constraint a text can impose?

Having the words was hugely liberating, but I didn't know that going into this project. I thought that it might be very difficult for me to write with that new limitation, but it was completely the opposite. Like you say, it was a relief not to have a blank canvas. The poems inspired me, and furthermore, it was almost like they told me what they wanted to be. They were like my muse. I miss writing to poetry now that I'm back to writing for the band. I will say this—I looked at a heck of a lot of poetry that I didn't feel a thing from musically. Ted Kooser's poetry is perfect for me. I wish I could write music to his poetry for the rest of my life. It's the whole world he creates; it's the world I come from. It's like going home to the most idyllic aspects of home.

3. Even though you've incorporated vocals into your recordings in the past, specifically Luciana Souza on a small number of pieces on 2004's Concert In The Garden and 2007's Sky Blue, Winter Morning Walks adds a much greater vocal dimension to your music, though of course the development is a natural outgrowth of the project's text-based nature. Was it a greater challenge to compose the vocal melodies on the Winter Morning Walks compositions as opposed to, say, lead melodies for instrumental voices?

Honestly, the vocals on my other music were, for the most part, an afterthought. I didn't write the music with that in mind, with the exception of the third part of the “Bulerías” recorded on Concert in the Garden. Then I started thinking about it a little bit more in the Sky Blue music, and occasionally now when I'm writing, I just hear Luciana's beautiful voice singing the lines. I haven't yet decided if I'll do that again on this new album. It just depends where the music goes.

4. Were you ‘hearing' Dawn Upshaw's voice in your mind as you were composing its pieces and tailoring the material to specifically suit her?

I absolutely was hearing Dawn's voice in my mind when writing the music for Winter Morning Walks. And, as much as hearing her gorgeous sound, I was hearing her amazing diction and wonderful sincerity of her delivery. Dawn is just so completely ‘human' when she sings. I love that about her; her sound is just so real and unmanufactured sounding. What a joy it was to write for and to get to record that voice.

5. Every listener will experience different associations in response to a particular work. As I listen to the two works featured on Winter Morning Walks, I experience associations with Villa-Lobos, film noir, and Piazzolla in response to the second one, while the title piece evokes associations with Robert Frost and Aaron Copland's Appalachian Spring. In the release's liner notes you discuss the second piece's connection to Brazilian music (though you're also careful to clarify that you weren't attempting to turn the “Brazilian poems into Brazilian music” and that “(t)he only poem set with direct Brazilian musical influence is ‘Quadrille'”), which makes me curious about what other associations the two pieces might have for you.

Honestly, I never write music imagining any particular musical influence. I do now hear that the first movement has a little bit of something Villa-Lobos in it. I think that the second movement has a little something that reminds me of Puccini, yet I don't even know which Puccini. The fourth movement, I was definitely going for the drama of flamenco, so that was truly intentional, but it's about a style, not any particular composer. And the last movement, yes, I think you are right, it has a little bit of unintentional Piazzolla in it. But then it also has a little bit of Brazilian Choro in it—a little bit of influence from Egberto Gismonti, although I don't know that he would hear that way. That reminds me of something that happened years ago. I wrote an arrangement of “Days of Wine and Roses” that I really felt was very Brookmeyeresque. When I pointed that out to Bob, he didn't have any feeling of it reminding him of anything he'd ever written—and I was scared I actually came too close.

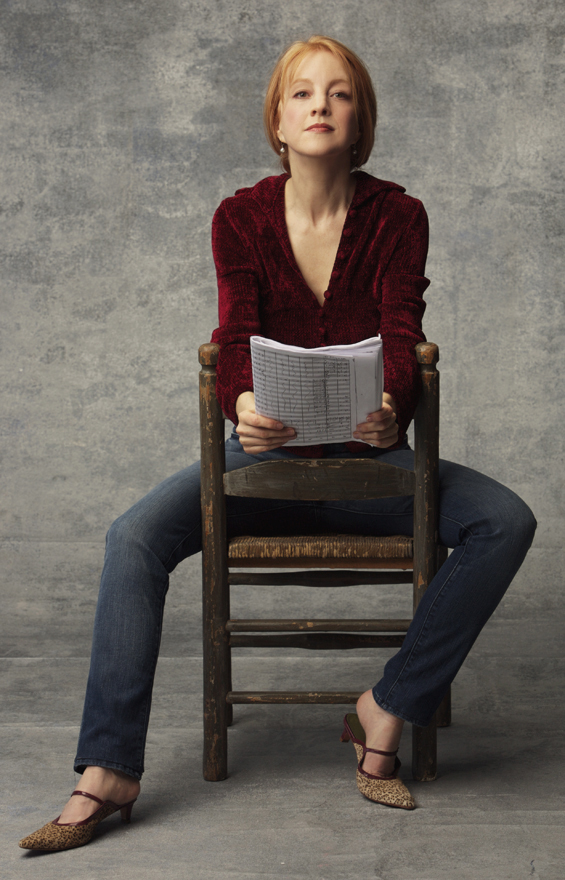

photo: Dani Gurgel

6. It's interesting that you incorporated the playing of three of your musicians into the arrangement of the title piece yet didn't do the same in the second. Why did you choose to arrange the second piece for the orchestra alone?

The second piece was actually written first. It was commissioned by The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, and the instrumentation was pretty much set. After conducting the piece in concert three nights in a row, there was an aspect of performance that I have with my band that I personally was missing. It wasn't the fault of the orchestra, they were spectacular. But it was the nature of writing music that had absolutely no improvisation. After performances, I'm very used to hearing musicians celebrating all the great creative moments that just happened in a concert. I'm used to experiencing the thrill and joy of that myself. In concert, it's really fun to literally watch everybody in the band appreciating each others' creative moments. So, when Dawn asked me to write another piece for her for the Ojai Festival while we were sitting at breakfast the morning after our last SPCO concert, I had already been thinking all night how much I would love to write for Dawn again, but to do it with some element of improvisation. That was the birth of Winter Morning Walks. The musicians in my group all have a keen sense of improvising in a way that doesn't just have to feel like the language of jazz, so I knew they would be able to make the improvisation sound seamless to the music I would write, and not like jazz plopped on top of classical. I wanted to avoid that pitfall at all costs.

7. Without wanting to turn this interview into a People profile, I'm curious as to what a ‘Day in the Life of Maria Schneider' might look like. Are you one of those ultra disciplined artists who resolutely sits down every day for a set number of hours to produce a set amount of work?

It's going to be a bit of a boring and depressing response. Unfortunately, I have to report that because of the nature of the business amidst the Internet, I spend a huge part of every day of my life doing business, probably 70% of my life. I run a jazz orchestra, publish my own music, produce my own records, and raise money for the records through my ArtistShare website, which is a very extensive website. I document much of my creative process to give fans an experience of being inside the music-making, record-making experience. That's basically the model of ArtistShare. And the success I've found through this has afforded me to be able to make records that are now costing from $150,000 to $200,000 a piece. I unfortunately have to waste a lot of time battling companies that are selling or sharing my music illegally on the Internet.

Besides all of this, I plan gigs, and I do clinics and guest-conducting. I tend to go through spurts where I write music intensively and just let everything else go to pot. I wish that I could get up early every day, carve out time and be on a schedule, like back in school, but my life just isn't like that. I have to put out a lot of fires some days, and other days things afford me more time for writing. I'm devoting more and more time to advocating for music creators in regards to laws and issues in relationship with the Internet and various changes in our culture's view of creative work. This is becoming increasingly important to me. When I go teach and students ask how they can do what I've done in their careers, I'm now at a loss. In the economic environment in regards to the Internet and technology, I don't have an answer. Right now, if there isn't a serious change of course, all I can predict is doom. It's very complex and deeply frustrating.

8. Are there specific things you like to do that are non-musical in nature?

I sit on the board of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, and the most fun thing is that I'm on the board for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. That brings me to the other great life love of mine, which is birds. I'm very passionate about the environment, bird habitat, and birds themselves. So I do put a fair amount of my life into that world, too. I'm trying to find balance, but it's not easy with so many things going on every day in my life.

photo: Jimmy and Dena Katz

9. While you have created an impressive body of work over the course of your recording career, you've also not saturated the market with recordings. That is, we don't see an excess of Maria Schneider recordings being released annually; instead, considerable time elapses between releases, suggesting that you take a great deal of time to ensure that each one is of the highest quality and has met a high personal standard before making its way into the world.

Firstly, I would say that I think most people make waaaaay too many records. Oh dear, there is so much music out there, and it just makes people appreciate music less. I wish that most people would make far fewer records, and try to make them that much better. Music reflects life experience, and unless you're doing a little bit of real living between records, you won't essentially have anything new to say. On the practical side, as I said before, these records are hugely expensive to make. It takes a long time to write the music, develop the music, and then I have to raise all the money through the Internet. And increasingly, it's harder and harder to sell music, because so many now expect music for free. The other hurdle is people are just so inundated with music, so deeply saturated, that they don't desire to hear anything new. I remember in the old days, I was so hungry for new music. I couldn't wait to go to Tower Records and just expected to drop a bundle of money because I was so in need for music. Who could feel that way now? We're all choking on media coming at us through links, emails, and YouTube! It's really insane. It's all too much.

I also need the time between the records to do the teaching gigs and guest concerts that afford me to pay people that help me, to pay for my life, and to pay myself for a fund in case I don't make my money back on these records. I'm putting out a huge huge financial risk. Most artists are doing that. That's the thing that people don't understand. Artists are now taking on tremendous financial risk to make our own records. So when someone just goes and listens on You Tube for free or whatever, it's killing the artist. The pennies Spotify pays don't buy someone a latte, much less pay the cost of a recording. It's a joke. Most these businesses aren't in the business of music anymore. They're in the business of advertising and big data, and what they need is content, and lots of it. Musicians are being used and getting worse than nothing; their work is being diluted and devalued, and they don't seem to yet know it.

10. Where do you see all of this heading?

I don't know where this is all going, but it's not good. It can't sustain itself. Does everyone want every artist in the world just living on grants? I've taken great pride up to now in being a financially viable business as an artist. It pains me to think that my government won't stand up to companies who essentially have a business model of selling stolen goods. It upsets me that people don't see the obviousness of the theft. What more can I say? When will this stop? Wait until 3D printers destroy manufacturing companies, then everyone will get it. Or maybe everyone will let that go too, because they'll all be so excited they can print something at home that they used to have to buy. I don't know about you, but I never minded spending money on music. It was entirely natural and expected. And, we savoured it more. How did that change? All I can say is, musicians are the canary in the cave.

So, in answer to your question, being so very busy, I couldn't possibly do more records from a time or financial standpoint, even if I wanted to. Check in with me again in ten years. I myself am curious where this will end up—maybe with me running off permanently to band birds or something in some jungle completely off the grid!February 2014![]()