TEN QUESTIONS WITH CHRISTOPHER TIGNOR

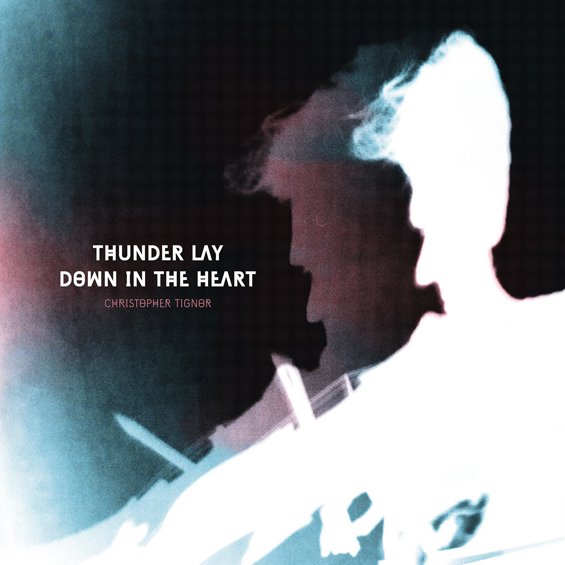

Christopher Tignor is a bona fide triple threat: he's an accomplished violinist, formally trained composer, and custom software designer (Mnemonica, MØØP, StreamSequencer). In addition, the New York-based Tignor not only releases innovative solo albums—2009's Core Memory Unwound and 2014's Thunder Lay Down in the Heart (both on Western Vinyl)—but has issued multiple full-lengths by his Slow Six ensemble (2004's Private Times in Public Places, 2007's Nor'easter, and 2010's Tomorrow Becomes You) and Wires Under Tension, his duo outfit with drummer Theo Metz (2011's Light Science, 2012's Replicant). The visionary manner by which Tignor integrates software into his musical practice is indicative of the imagination he brings to his work: in Slow Six, he samples and transforms the musicians' playing in real time, while Core Memory Unwound finds him presenting each piece twice, first in an acoustic arrangement for violin and piano and the second a ‘memory portrait' whereby custom software is used to generate a new version using live performance samples. Even more audacious is Tignor's latest release, Thunder Lay Down in the Heart, which includes a poem-based setting (featuring John Ashbery), a three-part work featuring the Boston-based string orchestra A Far Cry, electronic re-imaginings by Tignor, and an album-closing collaboration with Rachel Grimes (of Rachel's fame). Recently we had the pleasure of speaking with Tignor about the new album, his past association with LaMonte Young, influences, current listening, and future plans.

01. The press release for Thunder Lay Down in the Heart mentions that you worked in the ‘90s for LaMonte Young as an assistant. What was the experience like and did the association have a lasting impact upon you both personally and in your artistic approach? And is there still a relationship between the two of you?

I worked for LaMonte and his wife Marian for a couple of years right out of college. How best to describe the experience? It was certainly eye-opening and for a young artist meeting one of the founders of minimalism, certainly life-changing. LaMonte and Marian are incredible, giving people in so many ways, and I'll always be grateful for how they let me into their lives even for that brief window. While preparing their meals, fetching their laundry, and soldering broken fans back together (used to cool amplifiers), I overheard some great music and spent a lot of great evenings surrounded by the drones and colored shadows of their “Dreamhouse” installation on the floor above their loft in Tribeca.

They live an uncompromising lifestyle, the most well-known example perhaps being their extended twenty-eight-hour days (six in a week), phasing in and out with the rest of us.

The story I like best of all about LaMonte and Marian is how they were offered a deal with CBS in 1969 to record themselves singing drones over the sound of the Atlantic ocean—the waves crashing ashore. CBS funded this whole expensive session and then LaMonte and Marian decided they didn't like how the ocean came out and needed to redo it. CBS said they wouldn't do that, but LaMonte and Marian held their ground and CBS pulled the plug. I'm sure they knew that record could have exposed them early on to a much wider audience, but they were uncompromising in their aesthetics. You have to respect that—one of more punk rock moments in modern music, in my opinion. I haven't spoken to either of them in many years. I truly hope they are well.

02. The new recording also has much to do with associations of varying kinds. How did it come about that John Ashbery ended up recording a reading of his poem “A Boy” in his Chelsea apartment? Is he someone you've known a long time or is he someone you contacted with this recording specifically in mind?

I studied with John at Bard College when I was an undergrad there long ago. In fact, he was my advisor; at the time I was a creative writing major, though I was also involved in much electronic music, among other things. The poem came back to me years later while writing “Thunder Lay Down in the Heart,” and that line rang out as a title. I thought it would be a fantastic full circle to collaborate with John on a setting for this poem, written in the ‘50s that I then absorbed into my own work so many years later. Luckily, he was quite into how it came out. I admit, part of me was worried it could go the other way. I had a great chat with him the day we recorded it, which probably helped guide my sensibilities in a few subtle ways.

03. On the three-part title piece, you're credited with ‘memory machines.' Could you clarify what that means with respect to your contribution(s) to the piece?

I build software instruments that transform the sound of live performers in an attempt to create a new voice tangibly linked to the performers. I approach these processes by trying to get at what the 'essence' of a particular passage or texture might be that really interests me and use the electronics to dig that out of it and elaborate upon it, transforming it into something new. At the beginning of the title work, the string orchestra performs with a bowing technique I call 'elliptic bowing' that uses a circular gesture to create an airy sound that explores the overtones of the string. I wanted to dig deep into these overtones and see if I couldn't use them rhythmically, because the original playing is so arrhythmic—I thought the contrast would be an exciting why to rethink this technique in combination with the source. The result to me sounds like a sort of tanbura, maybe with some electronic tabla in there…

Because these electronic 'voices' are always derived from re-imagining events in the past, immediate or otherwise, I think of them as engaging tangibly with memory, sometimes over great distances. A digital computer's most defining aspect is its ability to store, to remember. I'll stop there...

04. The press info also describes “The Listening Machines” and “To Draw a Perfect Circle” as ‘electronic reminaginings and remixes' of the three-part title piece. Could you elaborate on exactly what you did to the original material to create the two related pieces?

There were many processes involved in each of these works. I tend to hone in on small gestures that pop out to me and build new pieces around them. “The Listening Machines” begins with a series of violin harmonics stacked in fourths that I slowed down by half. I used their resonances to create out-of-sync loops with very rough edges, so when the seam comes around you really hear the attack, like a bell. So basically I'm picking and choosing elements that I'm drawn to and that I think will make a new, compelling story.

The same is true for “To Draw a Perfect Circle,” but here I really wanted to explore how loops made from the soloist sections and then sped up could be used to build enveloping textures that sort of play with time a bit. I'm also playing with the sounds of “metal” versus the warm sounds of the bowed string in much of this work. To this end I dug deep into the percussion takes, likewise stealing phrases here and there that might speak to what I'd already stolen from the orchestra. It's an ongoing process of poaching and letting the sounds tell you what they need to feel whole in the new world you've built for them.

05. Please forgive one final reference to the info accompanying the album. Given that it cites figures such as John Adams, Aaron Copland, John Luther Adams, and William Basinski as reference points, I'm curious as to what part those artists in particular had to play in the album material.

There are so many artists that influence a work of this scale; I'd sort of take lists like that with a bit of a grain of salt. That being said…I've always admired John Adams' take on minimalism and his down-to-earth approach toward popular musical influences. There's a lot of both of that in this record, I think.

The first time this piece was performed it had a conductor and he made the connection in the first big melodic arc of the piece to Aaron Copland. I couldn't deny it. Those chromatic-friendly, rhythmically propelled themes do have that vibe.

John Luther Adams' beautiful sense of space, darkness, and mood has always rung true with me. I'd like to think the last section of the piece, amidst all its huge, stacked waves shares a kinship. Listening to Luther Adams' work has more than once made me think: hey, why not move to a really cold, isolated part of Alaska (or somewhere) and just light the place up with beautiful, loud textures all night?

William Basinski's dissolving tape loops share a sense of sadness (decay) as process and the pastoral that I think the middle section of the work benefits from. While the music doesn't dissolve (it is a work for live string orchestra), the electronics do often 'smear' the original roles in service of evolving transformation, an aspect I think he'd embrace.

06. Are there any composers and works, contemporary or otherwise, that you're particularly drawn to at the moment (what's on your iPod in other words)? And while you're working on a recording project, do you prevent yourself from listening to certain works or composers so as to avoid being overly influenced by them, or do you not worry about being so?

I am pretty protective of my musical psyche while writing. That said, if I refused to listen to other people's music while writing I'd never hear anyone else's music. But a lot of the time, I'll be listening to something because I think it specifically connects with a musical problem I'm trying to solve myself—research basically.

To that end I've been listening to a lot of Palestrina and early church music as well as religious music from other cultures. A bunch of Javanese Gamelan and Hindustani classical music and some online videos of the Muslim (Adhan) call to prayer.

I also heard Andrew Mckenna Lee's The Knells recently, which I quite enjoyed. Very strong compositions that sound so much like Andrew's distinctive voice. The performances and production are equally great.

07. Given your apparent interest in playing in multiple different contexts and with different people, I'm wondering if there are any artists with whom you'd most like to collaborate on some future project.

I'm mostly interested in pushing myself into music into new territories. I always enjoy working with choreographers and dancers if the fit is right, though there's always a bunch of logistical challenges that always seem to be news to them, so patience is required. Merce Cunningham and his studio's work is one I've always admired.

I can see finding a good fit with more poetry collaborations too. Again it's about much more than whether we like one another's work and more along the lines as to whether we think our work might resonate well together. (Do you have Mark Strand's number?)

08. Though in recent years you've appeared on recordings by Wires Under Tension and Lymbyc Systym, it's been about four years since the last Slow Six album Tomorrow Becomes You. Is the group still active and if so when might the next recording see the light of day?

Slow Six did a great show a few years back at the Ecstatic Music Festival when A Far Cry first played “Thunder Lay Down in the Heart.” I also created arrangements for AFC to play with Slow Six as well as This Will Destroy You who also performed that night. It's going to be hard to top that I think. These days I've been focusing on work under my own name, and doing more and more composing for other ensembles. But my crystal ball is busted—you can't be positive what's around the corner.

09. What's your take on the current classical-electronic field, which seems richer and more populated today than it's ever been? Do you feel some sense of vindication, given that Slow Six was creating a classical-electronic fusion years ago that was anomalous then but has become more commonplace today?

It's true that a Slow Six show was a very novel combination of elements in NYC's club scene, and thus probably almost anywhere, at the beginning of the millennium. It's also true that those superficial aspects—classical instrumentation side by side with rock instruments and laptops (I had to bring a desktop to shows for years; laptops weren't powerful enough)—is now pretty ubiquitous. But I think there's a bunch of deeper issues that Slow Six brought to the table that I see such bands struggling with. Rachel Grimes and I had some interesting chats about this: combining the act of composition with a culture of popular musicianship that expects to invent—and thereby 'own'—their own parts is a bit of a trick, to put it mildly. This extends into all sorts of both musical and extra-musical issues.

Slow Six was always a live band first and foremost. Part of our thing was that it could all be done in front of you; it was a living culture of people making music together, not some work-for-hire studio fabrication. Music now more than ever is a studio culture, and it's a different thing to just get your friend who plays cello to guest on your record (I've done this myself). Can you get that same guy to rehearse with you for like nine months before playing the work live? To me that's exciting. It's a slippery slope that is not for the faint of heart, and makes such bands much more likely to be studio projects first with a writer or two surrounded by hired guns for the live show. How that changes the musical results is its own, case-by-case question for each of us, I guess.

10. What other projects—recordings, touring dates, guest appearances—are currently on your horizon?

Alexander Turnquist has his first record coming out on Western Vinyl this spring I played violin on. It really sounds great with a wide range of instrumentation that really adds colour.

Right now I'm taking on a challenge I've never attempted in all my days behind the wheel: building a truly 'solo' set. So I've been holing up, building some new hybrid electroacoustic instruments, getting a bit of carpal tunnel from playing too much violin, and writing and burning a lot of music. It's a bit of a war. I'm constantly evaluating while playing whether this is the person I want to be on stage, whether this is what I think I want to say with my own hands at this point in my life. It's sounding like church music for agnostics, I must say. I'm variously resisting and giving in to instincts—constant personal revisioning.

March 2014![]()