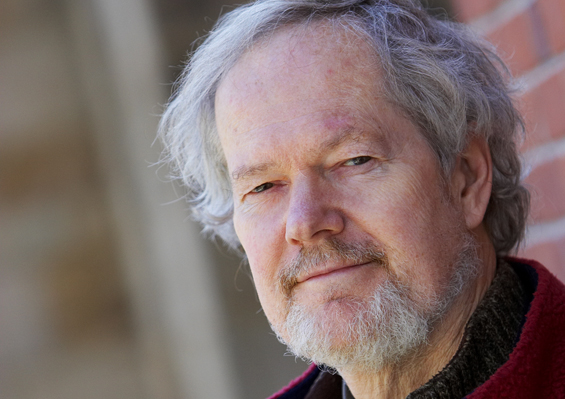

photo: Thomas McDonald

INGRAM MARSHALL: FIVE ESSENTIAL RECORDINGS

When American composer Ingram Marshall passed away on May 31st, 2022 at the age of eighty from complications of advanced Parkinson's disease, he left behind a body of innovative and distinguished work always marked by his indelible signature. The high regard with which he's held is indicated by memorial concerts given last fall at The Greene Space and the Yale School of Music where pianists Sarah Cahill and Timo Andres, violinist Todd Reynolds, guitarist Benjamin Verdery, and oboist Libby van Cleve paid tribute; that his recordings appear on labels such as Nonesuch, New Albion, and New World Records further testifies to that regard, as does the memorial article The New York Times published after his passing. He was also recognized with many awards and grants, including a Guggenheim fellowship.

Even so, the impression forms that Marshall has received less recognition than deserved. Scanning through my books on late-twentieth century American composers, chapters are devoted to Philip Glass, Steve Reich, John Adams, Terry Riley, and LaMonte Young, but Marshall's name comes up rarely. His name doesn't appear anywhere in Alex Ross's The Rest is Noise, for example; one would have thought that at the very least Fog Tropes, Marshall's best-known work, would have merited a mention. Such an omission is especially noteworthy when The New York Times' Adam Schatz called Marshall's music “some of the most stirring spiritual art to be found in America today,” said words written in reference to the 2001 Nonesuch release Kingdom Come. Of the books in my possession, Edward Strickland's American Composers: Dialogues on Contemporary Music is the only one that devotes a chapter to Marshall, the revealing interview in this case conducted in 1990. The composer's personal site includes links to more recent coverage, including a 2001 interview conducted by Frank J. Oteri at Marshall's home in New Hamden, Connecticut, and a small number of articles, interviews, and reviews can also be found online.

photo: Ingram Marshall

Marshall (b. 1942), who resided in the San Francisco Bay area from 1973 to 1985 and in Olympia, Washington, where he taught at Evergreen State College, until 1989, not only pioneered the use of tape sounds and electronic processing but did so in such a way that they are as integral to a composition as every other element. When extra-musical elements are included, it's because they're critical to the conceptual essence of the piece, and much the same could be said of Marshall's incorporation of Indonesian gamelan music. Nothing is done for mere effect, and every choice and gesture has meaning and purpose. While the music of certain other composers aligns itself readily to a particular genre category, Marshall's evades easy capture. Certain things do characterize his work, however, including expressivity, textural nuance, solemnity, and naturalness of development. In contrast to the process-based systems a minimalist composer might deploy, Marshall's creative approach was heavily guided by intuition and strengthened by a powerful emotional intensity. Indicative of that is the comment made by The Philadelphia Inquirer's Peter Dobrin, that “the first three minutes of pure orchestral music of Kingdom Come must be among the saddest ever written. It's more oppressive than Barber's Adagio while being every bit as delicate.”

Marshall's interest in electronic music emerged when he was a graduate student at Columbia University in the mid-‘60s and when he created his first tape pieces in a course taught by Vladimir Ussachevsky. In 1970, he moved west to study electronic music with Morton Subotnick at California Institute of the Arts and a year later spent three months in Bali absorbing Javanese and Balinese gamelan music. In the years following, Marshall combined his interests in Indonesian and electronic forms in works featuring the gambuh (a Balinese bamboo flute), analogue synthesizers, and tape delay techniques.

In contrast to many of his colleagues, the number of albums issued under his name is modest. His debut album, The Fragility Cycles, appeared in 1979 on IBU Records, that followed five years later by vinyl and cassette releases of Fog Tropes / Gradual Requiem (New Albion, 1984) and four years after that the same material reissued in an expanded form on CD as Fog Tropes / Gradual Requiem / Gambuh I (New Albion, 1988). Others followed with regularity: Three Penitential Visions / Hidden Voices (Elektra Nonesuch, 1990); Alcatraz (New Albion, 1991); Evensongs (New Albion, 1997); IKON and Other Early Works (New World Records, 2000); Dark Waters (New Albion, 2001); Kingdom Come (Nonesuch, 2001); Savage Altars (New Albion, 2006); and September Canons (New World Records, 2009). Single pieces also appeared in four collections: Fog Tropes on John Adams' American Elegies (Elektra Nonesuch, 1991); Sighs and Murmurs: A Sea Song on the DVD Immersion (Starkland, 2000); Gradual Siciliano (For Gus) on Cold Blue (Cold Blue, 2002); and Bright Kingdoms in The Voice of the Composer, New Music from Bowling Green Volume 7 (Albany Records, 2016). Whereas every one of the recordings issued under his own name could be deemed essential, the five that follow capture the remarkable scope and diversity of his work.

FOG TROPES

Whereas the four other selections are full albums, the first is a single composition, Fog Tropes, versions of which appear on Fog Tropes / Gradual Requiem / Gambuh I (New Albion, 1984) and on John Adams' American Elegies (Elektra Nonesuch, 1991). Given its importance to Marshall's oeuvre, it must be cited as one of the five essential recordings. Created in 1980-81, initially performed by Adams with the San Francisco Symphony, and later included in Martin Scorsese's 2010 film Shutter Island, Fog Tropes is scored for six brass instruments (two French horns, two trombones, two trumpets) and tape, the latter comprised of foghorn recordings Marshall gathered in San Francisco Bay. Being field recordings, other sounds appear with the horns, things such as birds, buoys, and wind. It first entered the world as a half-hour sound score created for performance artist Grace Ferguson's Don't Sue the Weatherman, but after the performance Marshall was struck by a section in the middle he thought was particularly memorable and so used it to produce a ten-minute tape piece. Adams, incidentally, conducts the version on American Elegies, but he's also credited as conductor on the New Albion treatment.

One of the more striking things about Fog Tropes is how effectively the brass instruments and foghorns blend, but that was no accident: in the interview with Strickland, Marshall reveals that he built the brass around the pitches of the foghorns. The effect he sought was for the brass players to sound as if they're on a raft drifting in the middle of a mist-enshrouded bay. The piece, which distills many of the signature qualities of his work into a compact statement, begins hauntingly and grows progressively more so. His patient shaping of the total sound mass is masterfully done, particularly in the way the material incrementally expands into a crushing chord at the four-minute mark. Disembodied voices wail in the background to intensify the unsettling tone until the piece slowly decompresses and vanishes, the gesture perhaps signifying the aforementioned raft disappearing into the mist. Testifying to the work's enduring appeal and importance, Fog Tropes II, a version for string quartet and tape, was created in 1994 and appears on the 2001 album Kingdom Come in a performance featuring Kronos Quartet.

THREE PENITENTIAL VISIONS / HIDDEN VOICES

A natural complement to Fog Tropes is Marshall's first solo recording for Nonesuch for the way tape loops and multi-track recording were applied to Three Penitential Visions (1986) and the processing resources of a digital sampler (the Casio FZ-1) were used for Hidden Voices (1989). Dedicated to Norwegian photographer Jim Bengston, the former work is in three parts, with the opening pair, “Eberbach I” and “Eberbach II,” followed by “Fugitive Vision.” It takes little time at all for the haunting side of Marshall's music to take hold when bird sounds, church bells, voices (the composer's, apparently) and tape loops of Bengston's saxophone playing blend into a blurry, ethereal mass in “Eberbach I,” and the engrossing quality of the material remains firmly in place for the full eighteen minutes of the opening parts (the titles for the parts derive from Kloster Eberbach, a monastery in Germany's Rhine Valley that Bengston and Marshall happened upon when they were touring Alcatraz in 1984 and from which they gathered sounds and images). “Fugitive Vision” distances itself conspicuously from them in presenting a dense, ever-burbling stream of acoustic piano and analogue synthesizer patterns.

For Hidden Voices, which Marshall dedicated to the memory of his recently deceased mother, the composer coupled old ethnographic recordings of Eastern European vocal laments with a live performance of soprano Cheryl Bensman Rowe singing “Once in David's City.” Alongside the processed vocal elements, Marshall added bells (recorded in Bellagio), his own voice, and various other voice- and bell-like sonorities. While six sections are identified, the piece unfolds without pause for nineteen tension-filled minutes. As compelling as Three Penitential Visions is, the greater work is Hidden Voices for its stirring lamentations, Rowe's vocalizations, the boldness of Marshall's processing treatments (witness the vertigo-inducing screech that arises fourteen minutes along), and his masterful shaping of the piece. The unforgettable closing section, ablaze with bell strikes and chills-inducing vocal supplications, is among the most beautiful material Marshall created.

In his interview with the composer, Strickland expresses reservations about “Fugitive Vision,” specifically what he regards as the incongruity of its levity compared to the weightier “Eberbach” parts; Marshall's rejoinder is that the third part “provides an escape, a release of tension.” Strickland does have a point—there is an undeniably stark difference between the two sections—yet the difference isn't so great that it undermines the work nor the impact it has. Both it and Hidden Voices are, like so much of Marshall's music, mesmerizing.

ALCATRAZ

Alcatraz is a kindred work to Fog Tropes and the “Eberbach” parts of Three Penitential Visions for the fact that the San Francisco Bay setting is central to both Fog Tropes and Alcatraz and because of Bengston's pivotal collaborative role in the latters's creation. Rather than sound design alone conjuring a place, Alcatraz presents Marshall's music with Bengston's photographs of the island. Consistent with the project goal articulated in the composer's liner notes, the subject proved to be one that “the photography and the music … separately illuminate.” To create the work, the two visited the site on numerous occasions over a two-year period, Bengston gathering photos and Marshall, armed with a tape recorder and microphone, collecting sounds of buoys, birds, and fog horns as well as recording singing and gambuh flute playing in some of the prison's resonant spaces; acoustic piano is also central to the composition. One of the recording's most memorable sounds is, of course, the roar of the cell doors slamming shut; in his estimation, “this chorus of metal echoing through the wildly reverberant space of Alcatraz is probably the perfect sound print of the desolation and utter finality of the place.” In the New Albion release (Starkland issued in 2013 a DVD iteration featuring Alcatraz and Eberbach), the photos guide the listener on a tour into the prison and out, with the music and imagery synchronized to reinforce that sense of a visit to and from the site. Just as the waters of the bay surround the island, so too do a ghostly ambient-styled prelude and postlude frame the work proper.

All subdued atmospheric elements and softly tinkling pianos, “Prelude—The Bay” readies the listener for arrival to the island. After an insistent array of piano and synthesizers rolls through the “Introduction,” the arrangement largely strips down to piano for “The Approach,” the section memorable for the haunting melodies Marshall crafted for the movement. Moving inside the prison, footsteps eerily resound and cell doors close mercilessly, the action as brutal as a gunshot. One of the work's many fascinating aspects is how successfully Marshal combines natural and electronic elements, one of the latter's more arresting details being the manipulations that turn the words “rules and regulations” into a woozy warble in the recording's fifth track. Following the spiritual desolation of “Solitary,” the uplifting radiance generated by echoing pianos and synthesizers in “Escape” and “End” comes as a relief. Constructed as artfully as Fog Tropes and Hidden Voices, this “recording-photo album” is one of Marshall's most memorable creations.

EVENSONGS

With Evensongs featuring two largely acoustic works performed by The Maia Quartet and a wholly acoustic one by The Dunsmuir Piano Quartet, the release must have caught a few Marshall followers by surprise when released in 1997. Yet while it does clearly distance itself from earlier works on sound design terms, his distinctive sensibility as a composer is very much present, despite the change in instrumentation. And the release doesn't signify a total break from previous ones when Entrada (At the River) amplifies the string quartet's playing with electronic delays and a bit of a tape collage interjection surfaces in Evensongs, the voice of Marshall's then five-year-old son Clement. By the composer's own description, the work is “a reflection on the mirror of childhood one sees in one's own children.” Realized magnificently by The Maia Quartet, Entrada entrances for the disarming beauty of its mournful expression.

After Evensongs returns us to childhood via music box tinkling, the string quartet takes over, this time executing an emotionally powerful and at times rapturous work presented in two three-part sections under the subtitles Steal Across the Sky and Fast Falls the Eventide. While the piece as a whole generally perpetuates the elegiac tone of the opener, an occasional folk-tinged melody and dance episode varies the mood. In My Beginning is my End, its title drawn from T. S. Eliot's Four Quartets, finds The Dunsmuir Piano Quartet concluding the release with a ravishingly lyrical, at times hymn-based work in two parts. If Fog Tropes, Hidden Voices, and Alcatraz represent some of Marshall's most audacious creations, Evensongs is the easiest one to embrace, not necessarily because of its acoustic makeup but for featuring some of the composer's most enchanting melodic material. The exceptional performances by the two ensembles is also certainly a key reason why the recording has the impact it does.

DARK WATERS

Acoustic and electronic realms merge again on Dark Waters, as beautiful a recording as Evensongs in large part because of the collaborative role Libby van Cleve played in the project's creation. While its three compositions are of course credited to Marshall, her English horn and Oboe d'Amore playing on two pieces is critical to the music's impact. In fact, the title work was written for her in 1995, and when that collaboration proved so satisfying the two reunited four years later for Holy Ghosts, a three-part work based on motives from a Bach aria. For Dark Waters, Marshall turned to Tuonela, the tone poem by Sibelius that musically depicts a swan gliding over the waters separating the world of the living from that of the dead. While Marshall's composition is a kind of homage to the Finnish composer (the tape material was created from an old 78 rpm recording from the 1920s of “The Swan of Tuonela”), it ultimately registers as a Marshall creation full stop when van Cleve's English horn is processed through digital delay devices and mixed live with the tape material. The English horn-and-electronics combination proves riveting, especially when the tone of the material is sometimes foreboding and verges on sinister.

Live digital delay processing was also applied to Holy Ghosts, with this time van Cleve playing Oboe d'Amore and the music spellbinding when her instrument multiplies into an entrancing swirl. The album's closing piece is Rave (1995), which Marshall created for choreographer Paula Josa-Jones for her solo dance work Raving in the Wind. As the imagery in that piece is largely avian-oriented, Marshall turned to bird calls and specifically those of loons and, yes, ravens for inspiration; his interest in gamelan also found its way into the piece also via samples of southeast Asian instruments. As always with a Marshall creation, startling moments arise, in this case sounds of bird wings violently flapping and a maelstrom of screeching and shrieking.

That none of the albums Marshall released after Dark Waters—Kingdom Come, Savage Altars, and September Canons—was deemed to be as essential as the five chosen shouldn't be misconstrued. Any of those later releases could have claimed a spot, particularly when they include key Marshall works performed by artists such as pianist Sarah Cahill, Theatre of Voices, guitarist Ben Verdery, The Tudor Choir, and violinist Todd Reynolds. The five that were selected, however, collectively speak to the remarkable breadth of his output and the visionary spirit responsible for its creation.

website: INGRAM MARSHALL

February 2023![]()