Lukas Foss: The Jumping Frog of Calavares County

BMOP/sound

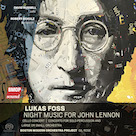

Lukas Foss: Night Music for John Lennon

BMOP/sound

With its discography now in the triple digits, conductor Gil Rose and his Boston Modern Orchestra Project (BMOP) present not one but two volumes of audacious material by Lukas Foss (1922-2009). The releases, 131 minutes in total, could have been packaged as a double-CD set, but in presenting them separately Rose and company grant listeners multiple purchasing options. Certainly familiarity with the volumes' contents might induce some to lean towards the opera volume and others the instrumental set. Regardless, the two offer a collective portrait that speaks to Foss's panoramic vision, his idiosyncratic sensibility, and the fecundity of his imagination. This isn't the first time, incidentally, Rose and the BMOP have presented Foss's music, with treatments of his oratorio The Prairie and Foss's symphonies appearing in 2008 and 2015, respectively.

The Berlin-born prodigy came to America in 1937 and initiated studies at Philadelphia's Curtis Institute of Music at the age of fifteen—though by then he'd already been composing for eight years. Sixteen later, he would succeed Arnold Schoenberg as Professor of Composition at the University of California and embark on producing a vast array of innovative music. While the sum-total of material he created far outstrips the five pieces on the two volumes (Megan Stahl notes in her commentary, “As a composer, conductor, pianist, and pedagogue, his creative output spanned half a century and more than one hundred musical pieces”), they form a representative microcosm in spanning a robust range of compositional styles and practices. Foss wasn't immune to being influenced by the music that came before him, but he was ultimately a true original, someone who couldn't be anyone but himself (he wrote, “Invention does not fall upon a blank mind”).

The vocal set precedes The Jumping Frog of Calaveras County (1949) with Introductions and Good-Byes (1959), at nine minutes maybe the shortest opera on record; just shy of forty minutes, the also one-act titular work is refreshingly compact too. As much musical theatre as operatic works, they're entertaining, not to mention cheeky, witty, and at times hilarious. Free of the aleatoric dimension that complicates matters on the other volume, the settings on the vocal release are wholly through-composed and brilliant on compositional and orchestration grounds. Probe beyond their chuckle-inducing surfaces and you'll find writing of tremendous sophistication and imagination.

Scored for one lead vocal role, nine non-singing stage roles, an off-stage vocal quartet, and pit band, Introductions and Good-Byes weds music by Foss to a clever libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti and features a terrific performance by baritone Thomas Meglioranza as the Host. Ostensibly a musical rendering of a cocktail party that sees nine guests arriving and departing, the work advances from a brief instrumental scene-setter “Outer Curtain” into a full-blown series of, yes, greetings and farewells during “Inner Curtain.” Though Howard Taubman deemed it “a diverting trifle” when he reviewed it for The New York Times after its 1960 premiere, the piece has much to recommend it, especially when it skewers the social etiquette of the upper crust with mockery but gently, not cruelly. Even so, shallowness of social interaction is clearly implied when the libretto comprises nothing more than the guests' names. As Stahl wryly observes, in “prioritizing propriety above substantive conversation and meaningful connection,” such interactions become merely “another genre of performance.” It's Foss's brilliant integration of the vocal and instrumental elements that impresses mostly, however, and the deftness with which he overlays voices, folds extra-musical details (such as the doorbell) into the musical fabric, and matches the musical writing to the libretto are wonders to behold too.

Funnier still is The Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, based, of course, on the Mark Twain short story. Scored for seven voices and orchestra and with a libretto by Jean Karsavia, the work frames two multi-part scenes with a spirited overture and finale in its single-act design. In simplest form, the tale concerns the hoodwinking of Jim Smiley (tenor Neal Ferreira), a local gambler whose frog, Daniel Webster, has been trained to jump to record heights, by an itinerant con artist (bass David Salsbery Fry) called The Stranger (“Each time I hit a town, I do the same: I shake some sucker down and jump the blame, find me a woman and give her the eye, then thank ye kindly Ma'am, and it's good-bye”). Rounding out the cast are baritone Isaac Bray as Uncle Henry and mezzo-soprano Felicia Gavilanes as his niece Lulu, with others personifying a guitar player and assorted townsfolk. After Smiley accepts the Stranger's bet that he could coach an ordinary frog to beat Jim's in a jumping contest, the Stranger secretly loads Daniel down by feeding it buckshot and vamooses after pocketing the winnings. When the frog vomits the buckshot, the trick is discovered, the Stranger dragged back to town, the money returned, and Daniel again celebrated as the frog-jumping champion of Calaveras County.

A number of things distinguish this rendition, but first and foremost is the deft delivery by singers who infuse their customary operatic style with a folk-like twang appropriate to the American West setting. It makes for an arresting combination when Foss's contemporary musical gestures blend with a tone consistent with the milieu of Twain's tale, and while a palpable tension results, it's not off-putting. Ferreira, Fry, Bray, and Gavilanes deserve mention for their terrific turns, as does the BMOP for its quicksilver accompaniment. A passage or two might call to mind Stravinsky's neo-classical writing or Copland's Rodeo, but the piece ultimately registers as a splendidly original creation by Foss. Once again the musical character is tailored to the libretto, with orchestration smartly matched to support the story action and mood changes.

Compared to the operas, which go down extremely easily, the second volume's a tougher nut to crack. At eighty-one minutes, it's considerably longer than the concise fifty of the first, but there is a reason for that length (more on that later). It begins straightforwardly enough with Night Music for John Lennon (1981), a work in two movements (though three segments are designated, a prelude, fugue, and chorale) that one might presume was written after the musician's murder on December 8th, 1980 but was in fact begun on the morning of that day. It doesn't crassly quote Lennon's songs but instead pays tribute indirectly and references rock and pop, albeit subtly. The fifteen-minute piece was commissioned by the Canadian Brass, who premiered it with the Northwood Symphonette at Avery Fisher Hall in 1981. An aleatoric dimension is woven into the fugue section where the conductor's afforded choices about instrument order but aside from that is through-composed. Opening prettily with a lilting solo piano part, the “Prelude” blossoms with the addition of a brass quintet and then strings and woodwinds, the mood generally serene though an ominous undercurrent is present too. “Fugue & Chorale” opens with jittery music of the kind Steve Martland would create decades later and grows progressively more tumultuous before eventually returning to the gentler pitch and chorale-like texture of the piano-based material with which the work began.

The other two are the thornier ones of the three as they include the application of aleatoric principles, in these cases Cello Concert (not concerto) (1966) and the Concerto for Solo Percussion and Large or Small Orchestra (1974). On this release, the former, composed for Mstislav Rostropovich (who premiered it at Carnegie Hall in 1967 with the London Symphony Orchestra and Foss conducting), augments its four formal parts with two alternate versions apiece of its second and third movements. In including these extra permutations, a more comprehensive account of the work is presented; it also, however, extends its twenty-three-minute running-time to thirty-seven. During the Cello Concert, the soloist, the remarkable David Russell in this case, moves in and out of musical “webs” of the orchestra and of a track pre-recorded by the soloist, which is played from offstage amplifiers. Devilry of different kinds emerges: the cellist sticks to a particular pitch in the first movement, for instance, but the listener's fooled into thinking the soloist has been liberated before realizing it's the amplified track that's broken free. Chance emerges in the subsequent two movements, though it's again the conductor who's given choices, with the soloist adhering to a through-composed part. A variety of “accompaniment” parts are available to the conductor as options, but, as noted by Eric Hollander in his commentary, the cellist might be too focused on the solo part to notice which choice the conductor's made when the soloist's music is so “fiendishly difficult.” Far more space than is available here would be required to list all of the trickery Foss works into the score, but Hollander does an excellent job of clarifying the different arrangements the work offers. The taped cello component—absent during the ultra-challenging middle movements—returns for the fourth, with references to J. S. Bach's fifth cello suite surfacing at the movement's start and conclusion; the serpentine interweaving between the live and taped cellists proves particularly engaging. It hardly needs be said that, in toto, Foss's creation sounds unlike any other work featuring the instrument in the soloist's role.

Chance operations are even more extensively invoked in the percussion piece, which, originally commissioned and performed by Jan Williams, features on this recording his student Robert Schulz. Words by Foss offer a tantalizing entry-point to the work in likening the soloist to “a magician, who walks around and wherever he is things … happen. He will, for instance, walk over to the timpani, where there is a regular timpanist, and play from the other side.” In contrast to the cello concerto, its music is more in the musicians' hands than the conductor's. Theatricality is again a factor, with Foss even providing staging and lighting instructions in the score, and the conventional orchestra presentation expands to include “saws, bells, electronics, shouts, and a Souza march.” The thirty-two minute rendering by Schulz and the BMOP ventures far and wide, and while it no doubt is best experienced with the visual element included this audio-only treatment commands the listener's attention throughout when it teems with so much unusual percussive colour (the “Cadenza” movement especially) and is so unpredictable. There are even times where this wild, blustery creation seems as much a piano as percussion concerto when the keyboard's insides and outsides are worked so prominently into the score, but woodwinds and strings play strong parts too.

Minus those extra Cello Concert movements, the release weighs in at an easier-to-absorb sixty-seven minutes. Certainly a compelling argument can be made, however, for including those extra parts, even if the overall momentum of the release is slowed as a result. Regardless, taken together the two volumes, arguably essential additions to the recordings of Foss's music currently available, present a fascinating mini-portrait of an intrepid and ever-adventurous figure who deserves to be regarded as an inspiration to composers—young and old—everywhere.April 2025