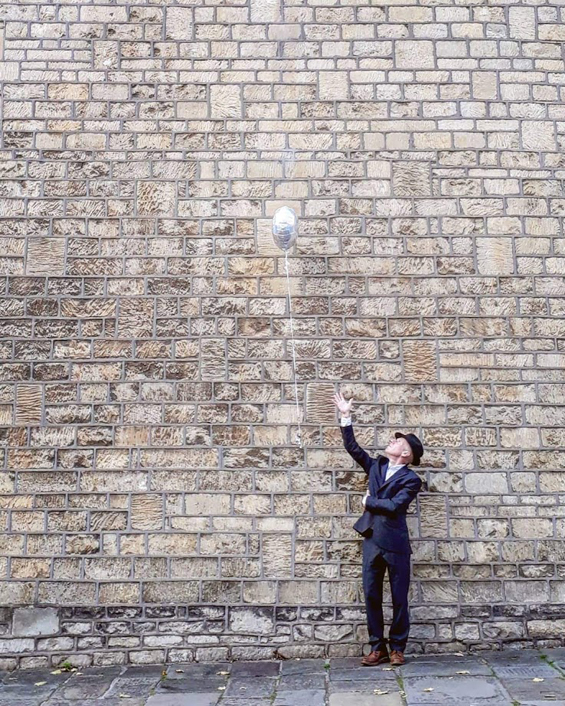

photo: Angela Coniam

BACKTRACKING WITH KEIRON PHELAN'S PEACE SIGNS

textura's had the great pleasure of reviewing many a Keiron Phelan-associated release, among them ones by Smile Down Upon Us and littlebow. Which makes Peace Signs, released under his own name, a major surprise, not just for being a song-based collection but for also presenting him in a lead vocal capacity (pulled off very handsomely, by the way). The release itself (reviewed here) is wonderful, filled as it is with songs of incredible variety and character, and the arrangements and performances are topnotch, too. So taken were we with it we humbly asked Phelan if he might consider sharing background details about the songs, which he very courteously agreed to do. We'll let the man himself take over from here...

Keiron Phelan: Peace Signs is, at heart, a songwriter album so may seem a strange beast to those acquainted with my predominantly instrumental history. What prompted this shift of focus was partly the song side of my work (alongside MoomLooo) on the second Smile Down Upon Us album. I simply remembered that I knew how to write songs and construct lyrical narratives; more importantly, I discovered I could sing with some real purpose. I did a lot of vocal work back in the ‘90s, but my voice was not at all a distinctive one and post-rock came calling for me, fortunately. Now, for better or worse, my singing has a far more notable quality.

I endeavoured to make an album in the mode of Bowie's Hunky Dory (a personal love) where the songs are stylistically disparate but still shape a cohesive body of work. According to some of the reviewers I've actually made a Kevin Ayers album sung by Edwyn Collins; I can live with that. Peace Signs does have a taste of the early ‘70s, not least in the sleeve art. That period chimes in with my late childhood, the point at which pop music was completely new to me and completely ‘mine.' I've tried to keep that freshness. The aesthetic also feels quite feminized, which seems to suit the mood.

One last thing; the band is really important. Singer-songwriters never seem to say that. Yes, I wrote the songs, but they wouldn't sound as they do, anything like it, without the band.

“New Swedish Fiction”: The most oblique lyric on the album, and the one I'm most proud of. I'd advocate for people to create their own interpretation; I'll try one, but I'm not sure if I'm doing us any favours. Here goes. A young couple who are poor and both dreamers. He tends to the shiftless, and she tends to create distance between them as a response. Sadly, the dissatisfaction with their circumstances bleeds into their relationship. Having each other isn't enough for either of them, and they don't really know their luck. I'm very taken with the characters of Kate Croy and Mertin Densher in James's The Wings of the Dove, and I suspect I'm fashioning an alternate version of the couple here. “New Swedish Fiction” is the dream world of the dissatisfied, where your ‘wrongs' can be violently ‘righted.' So, her escape is to picture herself as a scandi-noir heroine. Musically it's a very sparse song in a (I think) Tim Hardin style, and Ian Button's drum pattern is the essential part of the fabric.

“Peace Signs”: I'm rather trespassing on Jacques Brel territory here as I'm fusing mortality and romance. Life does many things but ‘making sense' isn't one of them. Watch your big schemes crumble and see how the world keeps turning, regardless. That sort of caper. So, this is very much a ‘no regrets' song, someone reflecting on his long ago, broken ideal-romance. It didn't work, it doesn't matter, life is nothing but an attempt at living. This is for all our ex-partners that never want to see us again. After all, they could be writing songs, too. Splendidly Rick Wakeman-esque piano (à la “Life On Mars”) from Jenny Brand, and Oliver Cherer and Brona McVittie's Laurel Canyon-style backing vocals are sublime.

“Satellite Hitori”: About a failure of communication. A few years ago the Japanese Space Agency (JAXA) sent a satellite called Hitomi into orbit. She very quickly got the technological sulks and stopped talking to Earth. I speculated that she got fed up listening to lots of boring messages from boring people to other boring people plus the fact that no one ever asked her what she was thinking about so decided to look for someone more interesting to talk to. I renamed her Hitori as the name means ‘alone' or ‘single person' (give or take). The moral of the story is: never take your satellite for granted. Gets rather Marc Bolan-ish at the end, with the unending chorus.

“Song For Ziggy”: Had Paul McCartney decided to pen a satirical, acidic, bubble-gum pop riposte to George Harrison's “My Sweet Lord,” this would have been it. Paul didn't, so I have. I'm a big McCartney fan. Even Jack Hayter's pedal steel sounds sarcastic.

“Mother to Daughter Poem”: A very kind reviewer claims that this “speaks beautifully of the nurturing relationships within a family set back in a far harsher time, in the early days of the Industrial Revolution.” I'd never thought about it that way but am delighted with his measuring stick. I like the way that David Sheppard's percussion section along with the clarinet and flute create a near Baroque atmosphere whereas James Stringer's electric organ, underpinning the whole, has an almost ‘60s jazz feel. A good synthesis.

“Apple Shades”: A light interval. Seeing a woman in yellow-hued September sunshine wearing green, apple-shaped sunglasses.

“My Children Just the Same”: Our man, here, is a shop-soiled Jesus. He knows his limits, he knows all the contradictions, and he knows that he certainly won't win. But he still tries. I like him. It's reminiscent of early Strawbs. The most singular thing about this collection of songs, for me, is the sheer number of references (critical or straight) to Christian belief. I'm a life-long atheist, so God knows where this is all coming from. I listen to Bill Fay, a lot. Let's blame Bill.

“Ain't She Grown”: This has been described as a wistful folk-rock song about the passing of time. Truth to tell, it's a very great deal darker than that. The narrator is a man who has, in the recent past, abused an underaged woman. She's now older and away from his malign influence. He's waiting to see if the police will come calling. I needed to make his feelings seem plausible as that (I believe) is one way that such people go about achieving their ends. His emotions are genuine. They are also 100% self-pitying and self-justifying. Don't waste a moment's sympathy on him. Well, I hope I haven't ruined that for anyone. They can't all be songs about nice people.

photo: Angela Coniam

“Country Song”: A near instrumental. Furiously channelling Lee Hazelwood. Hear that train whistle blow.

“Hippy Priest”: A lot of this album is about belief. People who think they believe in something or someone but don't. People who believe but too much. People who have a need to believe, and so on. The narrator of this song is someone who has chosen to be exceptionally credulous. He'll believe in anything, however nonsensical, dubious, or even objectionable (Desperate Dan, Piltdown Man, the Ku Klux Klan, etc), if it brings him a yard of social acceptance (doesn't matter much who with) or gives him the illusion of being grounded. He just can't take life's uncertainties. The Hippy Priest, whom the narrator admires, is a very smooth operator. Everyone wants to listen to him and be his friend. He's entertaining and makes people feel good and in touch with themselves. But, deep down, he doesn't really believe in any of it. He's just plausible and very good at it. A fun guy. It's a slightly Chaucerian conceit, and I was thinking of the way that in The Canterbury Tales Chaucer would sometimes nail a particular clerical type who was clearly in ‘the biz' for the all the benefits and not for the belief. Fourteenth century, twenty-first century, no change. Which brings us to....

“Canterbury”: This is where my cynicism departs, but we stay in the company of Chaucer. Canterbury, the traditional place of English pilgrimage throughout the Middle Ages, is a low-lying, very small city. If you walk down what is known as The Pilgrim's Way towards Canterbury its cathedral looks breathtakingly beautiful. It also looks absolutely enormous. And this in a time when we are surrounded by huge buildings. Imagine your first glimpse of it during a time when the largest building you'd even seen was one story high. The impression it made upon the Medieval eye must have been truly transformative. The chanted verse, here, is a section of Chaucer's own words from “The General Prologue to The Canterbury Tales,” and I simply attempt to share his exuberance at the advent of spring in England, his pilgrim character's (various levels of) religious devotion and their worldly pleasure in each others' company. The music starts with a variation on the Pachelbel's Canon, which seemed to be appropriate, and then develops through a number of mood-shifting sections. Pretty much the whole band on this one, stretching out into a slow country-tinged chorale at the end. As I said before, they're really important.November 2018![]()