photo: David Conte

FIVE QUESTIONS WITH DAVID CONTE

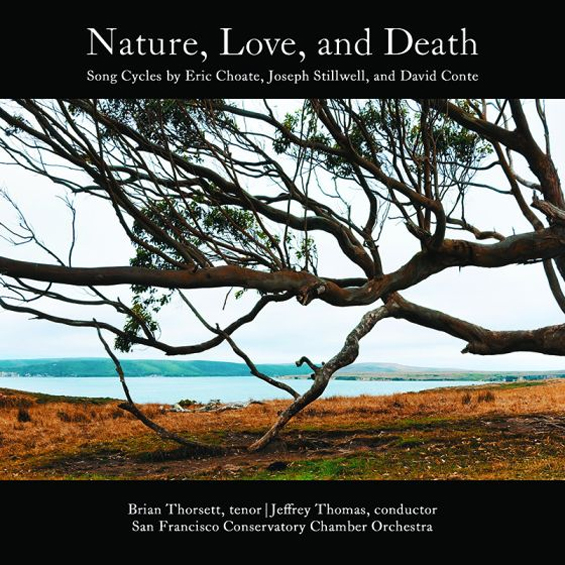

Visit the ‘Listen' section at David Conte's site and you'll find an abundance of vocal and instrumental excerpts remarkable in their quality and variety. As generous in number as they are, they're a modest representation of the more than 150 works the award-winning composer, born in 1955, has produced. Operas, choral and orchestral works, film scores, chamber settings, and art songs are among the pieces Conte has produced, and a solid number of them are available in recorded form, too, on labels such as Delos (Choral Music of Conrad Susa and David Conte), Albany (Chamber Music of David Conte), and Arsis Audio (Everyone Sang: Vocal Music of David Conte). A graduate of Bowling Green State University and Cornell University, Conte is Professor of Composition and Chair of the Composition Department at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. A sterling introduction to his work is the recent release Nature, Love, and Death: Three Song Cycles for Tenor and Chamber Orchestra (reviewed here), which pairs his American Death Ballads with song cycles by Eric Choate and Joseph Stillwell, all three splendidly performed by tenor Brian Thorsett, conductor Jeffrey Thomas, and the San Francisco Conservatory Chamber Orchestra. Conte kindly made time in his busy schedule to speak with textura about the new recording and other matters.

1. The booklet included with Nature, Love, and Death includes commentaries by Eric Choate, Joseph Stillwell, and you, the three composers whose works are presented, but it doesn't clarify how the project itself came into being. How did it happens that song cycles by the three of you came together for the release? Relatedly, how did it come about that tenor Brian Thorsett and the San Francisco Conservatory Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Jeffrey Thomas, were selected as the performers?

I have had a long working history with tenor Brian Thorsett, beginning in 2010, when he premiered my Yeats Songs for tenor and string quartet. In 2016, he sent me some anonymous American ballad texts from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and I composed for him my American Death Ballads, which won the 2016 NATS Art Song Composition Award; Brian and pianist Warren Jones performed them at the NATS Convention in Chicago. I composed my Love Songs for Brian in 2016; both the Ballads and Love Songs were recorded in my two-CD set Everyone Sang: Vocal Music by David Conte released on the Arsis label in 2018. I've also worked frequently with conductor Jeffrey Thomas since 1996; he recorded my one-act opera Firebird Motel in 2004 and has been a frequent collaborator. He also conducted the premiere of Joseph Stillwell's Songs of Love and Solace in its orchestral version in 2013.

In about 2000 I established at the SF Conservatory, where I started teaching in 1985, biennial composition competitions, alternating chorus with art song. This initiative grew out of my long and deeply held belief that all the rhetorical devices of instrumental composition grow out of spoken language and the conventions of dramatic story telling. One could also say: "In the beginning was the breath,” meaning breathing is behind all musical activity, and indeed all human activity, something that many features of modern technology are challenging. So both Joseph Stillwell and Eric Choate, who were my graduate students at SFCM, participated and won prizes in these competitions. I then encouraged them to orchestrate their songs. Brian Thorsett has always been extremely proactive in seeking out composers of art songs, and when he asked for some composer recommendations, I introduced him to Joe and Eric; our new CD of song cycles for tenor and chamber orchestra is the result.

2. Despite the fact that each song cycle concentrates on a separate title-related theme and that they complement each other remarkably well, they are nonetheless different, as they naturally would be when created by three different composers. What would you say are some of the things the cycles share as well as characteristics that differentiate each from the others?

Because of the twentieth century obsession with originality, often the matter of "musical lineage" is overlooked. My composition teacher Nadia Boulanger, with whom I studied from the age of nineteen to twenty-two in the 1970s, early on taught me,"True personality in music is only revealed through the deep knowledge of the personality of others." In that spirit, I teach my composition students to understand who their musical ancestors are, as I have done for myself, and of course part of their ancestry includes their teachers. Boulanger also said,"There are matters of technique that transcend style and taste." This has always been the focus of my own teaching, as I was taught by her: to emphasize a general approach to technique that involves the traditional disciplines of harmony, counterpoint, form, and orchestration. I like to think of this as related to training in architecture: learning how to build a building that won't fall down. One can look at buildings as seemingly dissimilar as Notre Dame and Disney Hall in Los Angeles, but there are certain structural principles in common behind both of them; the same goes for a Canata by Bach, and one by Stravinsky.

I would also say that all three cycles share features of natural prosody, and natural formal unfolding that follows both the structure and the character of the texts.

photo: SFCM

3. You've composed more than 150 works, including choral works, operas, chamber music, film scores, and works for solo voice and orchestra. Is your approach to composing a song cycle different from the one you might use to write, say, a chamber work, and if so how? Perhaps you could use of the four songs in American Death Ballads to illustrate the stages you work through when writing an art song and explain the reasons why you made the musical choices you did for that particular song.

As I mentioned before, for me all music grows out of a sense of the breath span and the melodic curves of speech, and story telling. Regarding vocal music, I have evolved a method for myself. Before beginning any setting of a text, I ask myself the following questions: who is the speaker, and to whom are they speaking? What kind of change does the speaker go through in the course of the poem, and where are the climaxes of realization of these changes? The answers to these questions guide me in choosing every aspect of the musical materials of the piece, including the tempo, metre, tonality, texture, and formal shape. In this way, the meaning of the text and the character relating the text "beams through" the music.

4. Your bio indicates that in 1982 you lived with Aaron Copland while preparing a study of his sketches, and you also studied with Boulanger in Paris, where you were was one of her last students. I'm guessing that these must have been transformative experiences for you. Could you give us some sense of what it was like to work with such influential musical figures as well as the most important thing you learned from each during your time with them?

I was so lucky to get to know Copland after my three years of study with Boulanger. I wrote an article for The Choral Journal about my summer in 1982 living at his house in Peekskill, New York, where I was studying his manuscript sketches for my doctoral thesis at Cornell University on his music (a link to the article is here).

So many readers will relate to the fact that a single teacher can change your life. That teacher for me was Ruth Inglefiled, a harpist and musicologist who was my music history teacher in my sophomore year at Bowling Green State University in Ohio; she sent me to Nadia Boulanger. Readers might be interested in a video where I explain her teaching methods (here).

photo: David Conte

5. You've composed an incredible amount of music and works of incredible range. Are there particular qualities they all share and that identify a composition as one by David Conte?

One of the great benefits of being a teacher for an artist is that it requires you to organize your knowledge. Because I experience that composition requires a degree of concentration and self-effacement in the service of something very high, I have given a great amount of thought to what constitutes a musical masterpiece. My definition sums up the guiding principles of my own work: A masterpiece represents a complete poise and balance between form and content, and between intellect and intuition. It unfolds with absolute confidence and organic naturalness, in that one cannot replace a single note or rhythm without altering the character of the work. The effect of masterpieces is that they communicate a level of concentration of thought and feeling that commands a certain attention from the listener, so that they enter into the world of the piece in such a way that they don't experience time in the absolute, chronological sense, but in an ontological sense, in some way "outside" of time, and their attention is held by the sets of relations established by the piece.

Bonus question: Your composer partners on the release, Eric Choate and Joseph Stillwell, are former students of yours who now teach alongside you at the San Francisco Conservatory. As you listen to their pieces on Nature, Love, and Death, do you detect traces of your influence on their compositional style and if so what would they be?

Again, the central tenet of my teaching related to composing vocal music is to serve the text. I experience my former students and young colleagues Joe and Eric to have achieved this completely in their settings and am very proud to share this disc with them.

website: DAVID CONTE

February 2023![]()