photo: Daniel Rotem

TEN QUESTIONS WITH DANIEL ROTEM

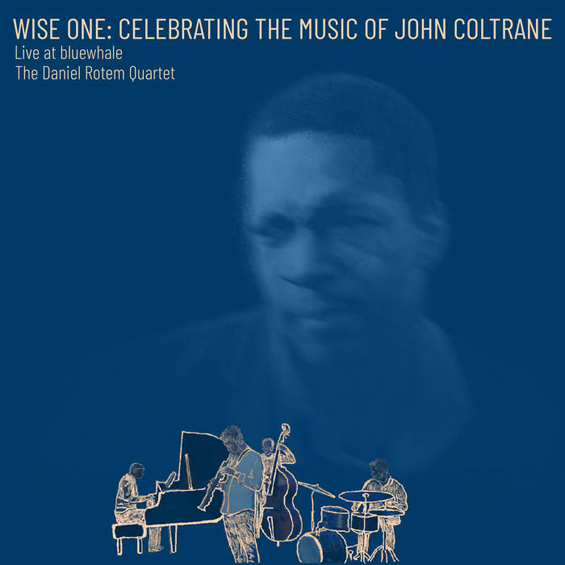

Daniel Rotem's initial exposure to jazz came about as a teenager learning saxophone at the Thelma Yellin High School for the Arts and the Rimon School of Music in his Israel homeland. As his passion for jazz intensified, so too did the desire to learn more and obtain the best possible education he could, desires that in turn led to tenures at Berklee College of Music and the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz Performance (now the Herbie Hancock Institute) and opportunities to play with Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Terri Lyne Carrington, Stevie Wonder, Lionel Loueke, and others. Rotem's since played around the world and even performed at the White House in 2016 as part of the festivities for International Jazz Day. He's also been active on the recording front, with highlights in his discography the 2018 double-album Serenading the Future and a late-2021 solo saxophone record created as a reflection on pandemic-imposed isolation. Rotem's current focus, however, is on Wise One: Celebrating the Music of John Coltrane, a live recording captured at blue whale with pianist Billy Childs, bassist Darek Oles, and drummer Christian Euman (reviewed here). It was this that formed the major part of a recent conversation textura enjoyed with the saxophonist shortly before the album's early April release date.

01. Most jazz tenor saxophonists pay tribute to John Coltrane by including a cover of, say, “Giant Steps” or “Naima” on their albums. You, on the other hand, have stepped completely into the ring with the heavyweight by releasing a recording entirely devoted to Coltrane compositions. What made you decide to take on what for many saxophonists would be an incredibly daunting challenge?

I would never dare stepping into the ring with Coltrane! If anything, I would be bringing him water between rounds, or supporting him from the crowd. Kidding aside, I must admit that I had never imagined putting together a “musical tribute band”—until I did. In my mind, everything I play and write is somehow a tribute to both the history of this music and the people who created it. In addition, composing my own songs and ideas was always at the core of my love for music and music-making.

My love for Coltrane's music goes back a long way. Growing up, my parents had a few John Coltrane albums that they would play, and I remember being drawn to the sheer power and focus of his sound. It wasn't until I started playing saxophone and studying at the jazz program at the Thelma Yellin High School in Israel that I began digging deeper into his music and recording catalogue. I'll never forget listening to Live at the Village Vanguard in jazz history class—it was hard for me! At the time I was listening a lot to saxophone players like Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Sonny Rollins, and Jimmy Forrest, and Coltrane's live recordings felt so intense! It took me a while, but with time I found great freedom, courage, and inspiration in those live recordings, and as you can imagine, I became a huge admirer and a dedicated student of Coltrane's music and playing.

While I read a few books about his music and life over the years (Ben Ratliff's Coltrane: A Story of a Sound and Lewis Porter's John Coltrane: His Life and Music are two very inspiring ones), it was after getting a copy of Coltrane on Coltrane, edited by Chris DeVito, in 2017 that the idea for this musical tribute started taking shape and form. Reading Coltrane's ideas about music, his thoughts on the potential music has, and his humility and dedication inspired me to try and take another look at his music. For six months I listened to nothing but Coltrane: starting from his early days with Dizzy Gillespie and Paul Chambers, I listened to anything and everything I could find.

02. The range of possibilities is huge when it comes to selecting Coltrane compositions, so how did you come to choose the ones you did for the recording?

I began looking for songs that I could approach from my own musical perspective. Thinking of how Coltrane would pick a tune and reimagine it using his own aesthetics and vocabulary (“My Favourite Things” and “Greensleeves” come to mind, but also new tunes derived from existing standards like “26-2” or “Satellite”), I allowed myself to do the same thing with Coltrane's music.

I wanted to look for myself in the music, and to reflect on how the music feels and what it means to us today—using Coltrane's songs as both the vehicle and the looking glass. Considering his own musical journey, I can only hope that he would have approved of my humble attempt to honour his music and legacy.

03. Given how towering his influence as a musician and spiritual person can be, how did you manage to avoid being drawn into imitation and hold onto your own sound?

As a saxophonist, I spent hours studying Coltrane's recordings, transcribing his solos, working through his compositions and harmonic progressions; to me, his genius is untouchable. I remember one of my teachers at Berklee, saxophonist and improviser Ed Tomassi, speaking about this once. I'm paraphrasing, but he used to say that for many musicians there's an aspect about their musicality that stands out: technical facility, sound and tone, compositional skills, spirituality, creativity, and so on. I remember he used to say that Coltrane is an example of a musician who had it all. That resonated with me then and believe that to be true to this day.

As you said, Coltrane is such an inspirational figure, it's possible that no other saxophone player in history has had so many tribute albums recorded in their name (perhaps with the exception of Charlie Parker). While I always enjoy and learn from listening to other people play his music, at the end of the day, no one can play Coltrane better than Coltrane; that is true for any and all musicians. We each have our own story, personality, approach, and sound, that set us apart. Rather than trying to sound as much like Coltrane as I can, I would love to continue to delve deeper into how I can sound more like myself, if that makes any sense. To me, there is more of an element of a tribute in that: rather than try to sound like someone else, I would do everything I can to honour their music while sounding as much like myself as I possibly can.

With so many tributes dedicated to his music, I wanted to try and do something different. I feel like in some ways playing the music again as it was originally recorded (but with new solos) is the easiest (and sometimes the most enjoyable) way to offer a musical tribute. In that sense, you get to elaborate on songs and forms that you study, and the music sounds somewhat similar to the original recordings, which provides great joy and is very rewarding. There is familiarity in that approach. On the other hand, to take a leap and try to rearrange and reimagine a piece of music means that all the comfort of knowing and studying the original goes out the window in a way. It's almost like learning a new composition that has never been played before.

04. Could you elaborate on your statement that you aimed to pay tribute to him by “approaching it from the spiritual side”?

Reading through his thoughts and ideas about the music, I realized that the only way I would feel comfortable about presenting a tribute project would be to honour more than just the notes and musical components. It would have to take aim at the spirituality and intellect that led to the creation of the music in the first place. In other words, getting down to the core of what made Coltrane's music his music, which is his personality, perspective, beliefs, etc.

For example, he said, “I play what I feel in me, and I hope that what I feel in me says something to the audience…what we feel deep in ourselves should be communicated to others.” Also, “my music is the spiritual expression of what I am—my faith, my knowledge, my being … when you begin to see the possibilities of music, you desire to do something really good for people, to help humanity free itself from its hang-ups.”

05. The musicians joining you (on tenor and soprano) on the project are Billy Childs on piano, Darek Oles on bass, and Christian Euman on drums. How did this line-up come together and what direction, if any, did you give them for performing the pieces you selected?

I feel fortunate and honoured that I get to offer this tribute with this exceptional band. I first met Billy when I was a student at the Monk Institute. A visionary pianist, composer, and arranger, he is a hero of mine, and really a jazz hero—a direct link to some of the people who played with Coltrane and learned from him. There's an edge to his playing that I can only dream of getting closer to in my own playing. Darek and I had never played together before “Wise One,” but I had listened to him and admired him from afar. I knew he was leading his own tributes to Coltrane's music, which made him an invaluable member to the spiritual tribute I was trying to create. We've shared and created music in numerous circumstances since. I've played countless hours with Christian; we were in the same Monk Institute band and went through a lot together. He's one of my closest friends and favourite musicians to collaborate with.

From the very conception of this project, this was the band that I had in mind, and so far, this musical tribute has only been performed when the full band is available to play. As a bandleader I'm committed to doing my best to make everyone feel as comfortable as they can to be themselves and do what they feel is right for the music. Of course, with musicians like Billy, Darek, and Christian there is no need for any instructions at all. No verbal direction that I can offer would come close to their experience, musicality, and intuition. I think the arrangements had some musical guidelines “built in,” but other than that, I always feel privileged to be a part of the musical journey this band goes on.

photo: Daniel Rotem

06. Having immersed yourself so deeply into Coltrane's world, did the project end up changing you in certain ways, spiritually in your outlook and physically in your approach to the saxophone?

For one thing, I often find myself thinking about his ideas in my day-to-day life. If I find myself struggling with something—a musical challenge or personal challenge—I now know that I can draw on his writings as I look for my own answers.

Here are a few quotes I find myself revisiting: “Keep listening. Never become so self-important that you can't listen to other players. Live cleanly… Do right… You can improve as a player by improving as a person. It's a duty we owe to ourselves.”

“I try to reach people who come to hear me, and I think that the other members of my group have the same concern. We're really not trying to provoke a state of hypnosis or anything else like that; we just want to reach the audience, to communicate with them, to make them feel what we do.”

“I want to be a force for good … I know that there are forces out here that bring suffering to others and misery to the world, but I want to be the opposite force. I want to be the force which is truly for good.”

07. You've produced to date a very interesting discography that includes the beautiful double-CD set Serenading the Future and the recent album of solo saxophone called, simply, Solo, and now there's this fascinating take on Coltrane. I believe that you already have another album or two in the works, so tell us what you can about that and when we might expect to see them released.

I love composing, playing, and recording! With every project I find myself learning new things and opening up to new ideas that I look forward to trying out and bringing to life. The feeling of sharing music with other people—realizing composed music, listening to each other, improvising, communicating, experimenting—it is an unparalleled feeling. I think of albums and recordings as part of a continuum rather than a single project—chapters in a book, if you will! Each album tells a story of its own, but they all inform and expand on each other. That's why I generally keep a few projects ongoing at once—they're chapters in the same book, if that makes any sense.

Right before the pandemic I made two records, Wise One: Celebrating the Music of John Coltrane that we recorded live at bluewhale and the other is a studio album of new original music that I composed featuring a core band of some of my favourite musicians and closest friends who are based in LA and with many featured guests. Because of the pandemic, many of the musicians recorded and overdubbed from home, and while the distance was challenging, it also provided new opportunities for collaborations and ingenuity. I'm very excited about how that album came out, and can't wait to release it, hopefully later this year.

In addition, I started making another new album a few weeks ago for a very special label run by Pete Min, an incredible musician and engineer who owns one of my favourite studios. For this one, I'm experimenting with a new approach to composition and am playing all the instruments! This is a new and ecstatic feeling; I find myself recording a part on bass, then playing some drums, then layering some saxophone parts. Pete does his magic with it all. It's a different process from what I normally do, especially since I am the only musician in the studio, and typically it is the human connection that lives at the foundation of my existence in music-making.

I'm also working on arranging, composing, and expanding what I hope will turn into the next volume of Wise One, this time recorded in the studio with a large band. I hear strings, brass, woodwinds, maybe some voices too—nothing scheduled yet, but it has been on my mind for a while.

photo: Daniel Rotem

08. You grew up in Israel and discovered jazz after starting to play saxophone as a teenager, a discovery that led you to travel overseas to study at Berklee College of Music and the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz Performance (now the Herbie Hancock Institute). In what ways did growing up in Israel influence the beautiful tenor sound you now possess?

That's very kind of you to say. Sound (or tone) has always been one of the most important things to me about music, and so I appreciate the compliment.

Sound is often spoken of in the context of creative music as something you need to find. I understand that approach, but I see it differently. Rather than having to find it, I believe we all have a sound of our own, that is already a part of us, from the most novice student to the musical master. Rather than search and find our sound, I think of it as an onion: we have to continuously peel the different layers, the things that stand in the way, to get to the core of our sound. Just like studying never ends, we always have more layers to work through to get to the core. I think our individual sound is a reflection of our personality and our perspective of what it means to be human, and so in that sense everything I experienced growing up in Israel directly affects my aesthetic and approach to producing my tone. A couple of weeks ago I showed a few of my students a video of Sonny Rollins where he talks about the idea that you can never master anything, that there is always more to go. There is great comfort and encouragement in that: the journey is never ending.

If I have to venture into more specific musical terms, I would say that listening has helped me tremendously in the process of getting more aware of my sound. Listening to many different sounds is one of the best and most inspiring ways to get more comfortable working with your own sound and tone. It's also important to learn to listen to yourself, without being too judgmental. I encourage my students to incorporate practicing long tones, and one of the most important elements of that musical exercise is to learn to listen to yourself. It's very meditative.

09. You've played with many a jazz great, including Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Terri Lyne Carrington, and Stevie Wonder. Could you share a few things that you gained from those experiences, not just musically but in terms the time you spent with the artists?

While I was at the Monk Institute, we had the good fortune of spending time with Herbie and Wayne (we also got to perform with them, but that's a different story). One of the things they both spoke about is the idea of improvisation as an art of living in the moment. Wayne asks, how do you prepare for the unknown? I feel like the pandemic pushed us all into dealing with that question—how to navigate the unexpected and embrace the uncomfortable, and turning poison into medicine.

10. Your 2021 solo saxophone record was a moving reflection on the period of Covid-related isolation that you and so many other artists had to deal with. In what ways did the time away from live performance and close interactions with other musicians have an impact on you as an artist?

At the time, making a solo album felt like a way for me to deal with the isolation and distance from everyone. I missed performing very much, and releasing a solo album felt like an alternative way to get closer to sharing music again. People have come up with many interesting ways to continue creating and sharing music. That is one of the most beautiful things about the creative music community—the awareness of being in the moment, listening, and then improvising something out of that—the human potential is infinite! As the world slowly opens up again, I hope that societies can remember how important it is to invest in art, and how vital to our existence art, music, and dance are. I hope that one day there will be an alternative to Wall Street, where people can invest in art. We need creativity that is not just rooted in innovation for the sake of progress, but also creativity that is sensitive, attentive, and aware. I believe this kind of creativity will help us face the challenges that we will face moving forward.

web site: DANIEL ROTEM

April 2022![]()